From Google Maps to Pokémon GO, without maps the world would not function. But how did we start developing them? Ritienne Gauci and Dr William Zammit take a look at historical maps to discover fascinating quirks about the Maltese Islands. So how were map errors inherited? And what is the connection between religion and maps?

Maps have immediate appeal. Some are elaborately engraved while others have a decorative style, which was particularly loved by early map-makers and which still is, by contemporary collectors. On the other hand, maps can be elegant and simple, similar to highly technical modern digital cartography.

Many have tried to explain the appeal of maps. The seventeenth-century Spanish author Saavedra wrote, that by simply looking at a map, one could ‘journey all over the universe […], without the expense and fatigue of travelling, without suffering the inconvenience of cold, hunger, and thirst’.

Cartography is also a visual medium of first-rate geographic and historical importance. Traditional history did not have much respect or use for the visual records of the past: in a reality where history consisted essentially of political chronology, the biographies of the great and mighty, and of momentous happenings, the place of maps remained in the realm of an antiquarian curio, and they were not considered important historical documents.

Cartography is also a visual medium of first-rate geographic and historical importance. Traditional history did not have much respect or use for the visual records of the past: in a reality where history consisted essentially of political chronology, the biographies of the great and mighty, and of momentous happenings, the place of maps remained in the realm of an antiquarian curio, and they were not considered important historical documents.

With the rise of a new genre of history, the crucial value of maps became evident. Over time the daily life of the masses became more important for historians as opposed to the great episodes of the rich and mighty. Maps from obscure periods are even more interesting for the evidence they reveal, normally lacking from traditional documentation.

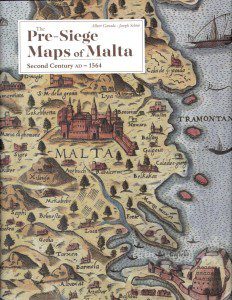

Albert Ganado and Joseph Schirò, authors of the latest Melitensia publication Pre-Siege Maps of Malta: 2nd century to 1564, have made a remarkable years-long commitment to Maltese cartography.

Ganado transformed his late father’s Melitensia collection into what is possibly the largest outside Malta’s national collections. His collection includes material that had been lost in the repositories of national memory. He has made a major academic contribution to the Maltese Islands by passing on the so-called ‘Albert Ganado Malta Map Collection’ to the National Museum of Fine Arts — a cultural treasure of international dimension.

The impressive map collection needed study. Maps carry the risk of being perceived simply as collectible items, due to their aesthetics and investment considerations. With his numerous studies, Ganado pioneered in the research of Maltese cartography, rather than leaving unstudied maps decorating a hallway.

Emeritus Chief Conservator Joseph Schirò is one of the most renowned professionals in this field. In the last years he has published a string of cartography-related publications with a landmark achievement being the founding of the Malta Map Society in 2009. The organisation is a young and modest cultural institution, but one which has already offered a series of publications, exhibitions, and lectures to the public, which have increased awareness of cartography’s academic significance.

“Albert Ganado transformed his late father’s Melitensia collection into what is possibly the largest outside Malta’s national collections”

The book, The Pre-Siege Maps of Malta, is a tour through the earliest cartographic representations of the Maltese Islands. Spanning over fifteen centuries, its invaluable productions are intimately connected with a historical narrative.

The work consists of a revamped modest, but pioneering study, originally published in 1986. Thanks to thirty years of research the number of Maltese pre-siege maps shot up from fourteen to forty maps, revealing delicious clues about medieval life. The Great Siege of 1565 is one of Malta’s greatest historical moments when an overwhelmingly large Ottoman army was repelled by Maltese militants and the Knights of St John. History prior to 1530 (before the Knights came to the islands) has generally been neglected. They lack documentary sources and can be historically perceived as an uninteresting, stagnant phase. But, documentation and maps now reveal otherwise.

No map can exist without its mapmaker. The colourful and informative book traces the life and times of the period’s mapmakers, engravers, and publishers. The authors tap into the genealogy of these pioneers, revisiting many aspects of their lives. Ganado and Schirò reveal the pioneers’ childhood, studies, and travels, while uncovering the cut-throat challenges of their work.

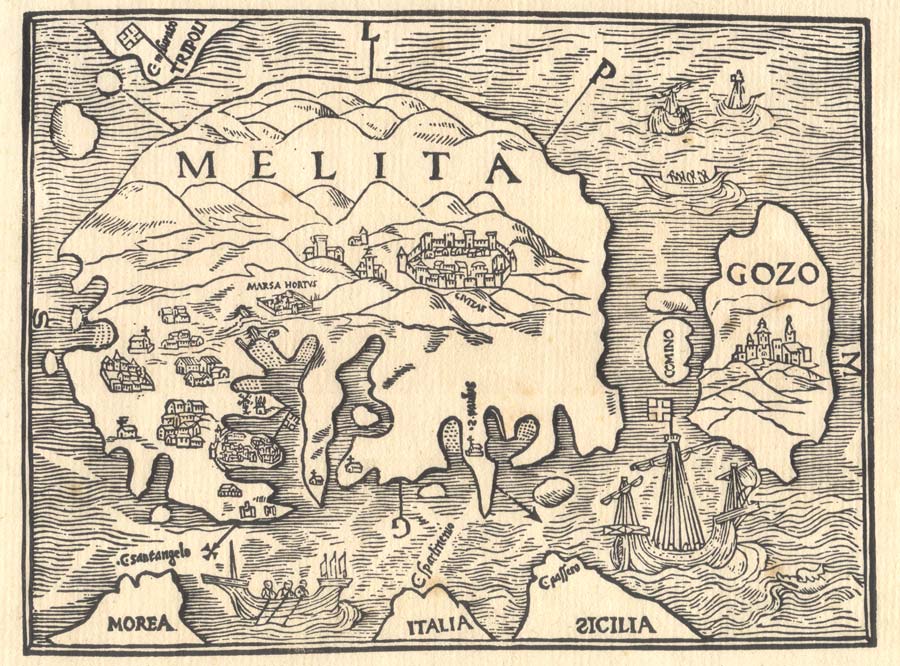

With geography at the core of map study, the cartographic genre ‘books of islands’, known as isolario, popularised island geography in this time period. These cartographic books combined maps and narrative-historical chorography. The Mediterranean region has 3,000 islands and became one of the most fertile avenues for the development of the isolari in the fourteenth and fifteenth century. Books by authors, such as Buondelmonti and Bordone, helped form Renaissance geographical concepts.

With geography at the core of map study, the cartographic genre ‘books of islands’, known as isolario, popularised island geography in this time period. These cartographic books combined maps and narrative-historical chorography. The Mediterranean region has 3,000 islands and became one of the most fertile avenues for the development of the isolari in the fourteenth and fifteenth century. Books by authors, such as Buondelmonti and Bordone, helped form Renaissance geographical concepts.

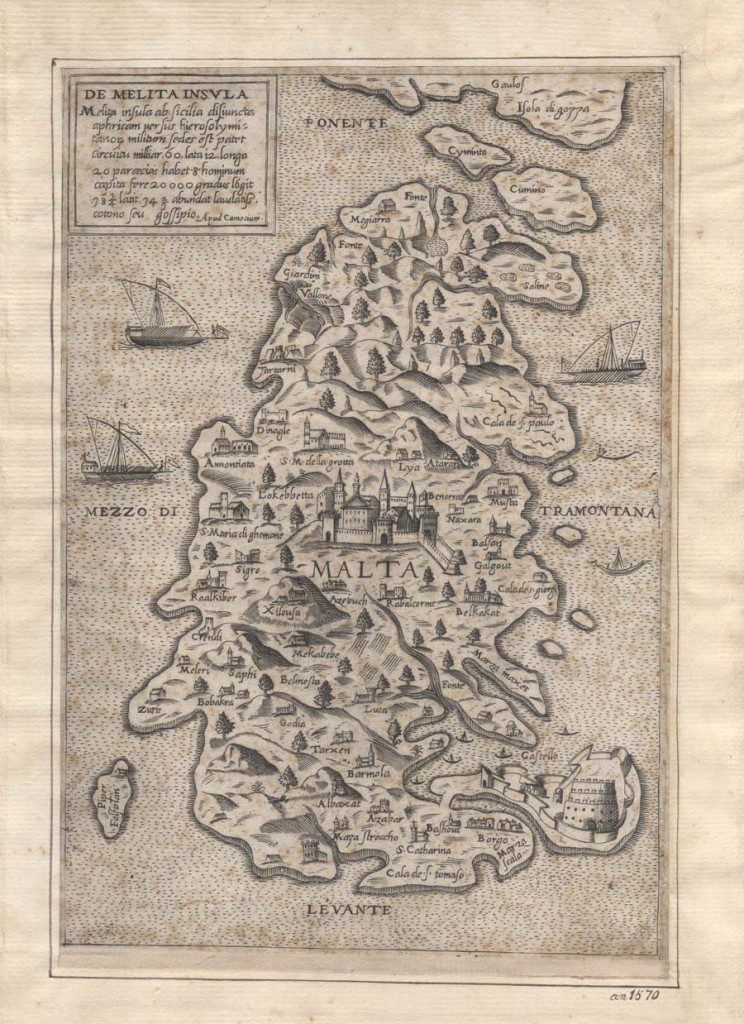

Maps intriguingly instill a desire in the map viewer to look out for familiar places or landmarks, such as their hometown or village. These pre-siege maps coupled with lengthy description, provide a detailed account of the earliest form of urban development in Malta. Johannes Quintinus’ map in 1536 identified seven villages that, barely two decades later, turned into twenty-nine place names as drawn by Gastaldi in his 1551 map Isola di Malta State 1. In his 1551 map, Antonio Lafreri introduces the concept of settlement hierarchy visualisation, with eight important places, names of towns and villages, marked in a small circle. Some of the place-names of these villages have now been lost to time. The cartographer indicated a town and village population size with the number of residences drawn. Hardly any population figures existed before.

Some maps also give a rudimentary sketch of the road network. The Lafreri and Bertelli maps of 1551 and 1552 show an elaborate web of major and minor roads. The Beatrizet map from 1563 provides a rare, possibly unique, visual layout of the road pattern around the developing harbour area just before the Great Siege.

Most maps of the period depict the fortifications of Malta and Gozo. These representations range from complete fabrication to remarkably accurate ones. The 1553 Foresti map erroneously includes Gothic towering spires and slanted roofs. The cartographer had no idea of Malta. Cock’s 1551 map, only known from its second 1565 state, depicts the harbour fortifications precisely.

The maps have other quirks. The 1536 Quintinus map shows the earliest-known image of Grand Harbour’s forbidding gallows at its entrance. They also show fresh water springs and a garden in Marsa.

These maps pleasantly remind one about the relative geographic inaccuracies of early maps. Distances between parts of the Mediterranean are reduced. In the 1536 Quintinus map Malta has its first map separate from the rest of the Mediterranean. Early defensive structures are wrongly sited, such as the Gozitan castello, incorrectly drawn on Malta on the 1470 Buondelmonti map. In the 1552 Antonio Millo map coastlines lose their physical proportionality to give importance to the main harbours of Malta. On the Dillingen map, the Paris Map, and the Marucelliana map of the mid-1500s, Fort St Angelo was awkwardly placed in the open sea due to map space limitations. There are many other historical quirks.

Yet, the value of these maps as a navigational tool remains pivotal and central throughout the book. Hazards to navigation are explained with the use of black crosses on shoals and red colouring for reefs; safe landings are marked by dots or tiny dashes at sea. The islands’ geographical characteristics, as portrayed in maps, are what attracted the Knights to Malta in the first place: the natural water features, sloping topography to landing sites, and large sheltering harbours.

These maps have no contour line representation yet land height is vividly sketched and coloured in a rather arbitrary manner. This provides a general idea of the islands’ hilly terrain. Remarkably, some hills were quickly erased from one map to another. In the 1551 to 1558 Gastaldi maps, Mount Sceberras became the city fortress Valletta.

Compass directions often radiate from these maps’ centre. Several transform the whole map into a compass rose, which leaves no doubt about the importance of these maps for navigational and military purposes. It is precisely on one of these compass points, where geography marries spirituality, with the addition of a small cross on the east cardinal point, to symbolically represent the direction to the holy city of Jerusalem. Other religious elements come out more strongly, such as the dramatic shipwreck portrayal of St Paul the Apostle (Ptolemy’s 1540 Munster’s edition of his Geographia).

But symbolism is not just a prerogative of Christian cartographers. The authors balance their work with fine examples of Islamic cartography, which in the book are best represented by the works of Piri Reis and Al Idrisi. The 1157 Al Idrisi map was oriented south (like most Islamic cartography), because many communities that lived north of Mecca in the seventh and eighth century faced south during prayers.

Through these works, the authors reveal to us a ‘medieval world’, which philosopher Charles Taylor famously referred to as an ‘enchanted world’, where the physical and spiritual were not so conceptually separated as they are today. In being so attuned to symbolism, Christians and Muslims drew maps to portray their symbolic interpretation of the world. Today’s maps lack such symbolism.

All this information is needed to interpret maps. Detailed analysis is needed for identification in libraries, future research, and comparison with yet undiscovered maps. These maps had a lasting influence, helping to shape the historical events that unfolded thereafter.

The complexity of research in maps in breathtaking. Perhaps the most fascinating element is how a single image manages to convey a diversity of delights to viewers from different walks of life. Cartography cuts across borders, and no one person is capable of embracing all of the enjoyment of maps.

The Pre-Siege Maps of Malta; 2nd Century to 1564 was published by the Malta Map Society (maltamapsociety.com) and BDL, and was sponsored by the Alfred Mizzi Foundation. It is available in hard cover format in all leading local bookshops.

Comments are closed for this article!