…was a murderer, brawler, and one of the greatest artists that ever lived. As he travelled from Rome to Malta, he inspired fellow artists in different regions who developed distinct styles. In Malta, he left some of his greatest artworks

When on 6th October 1608, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio escaped from detention in Fort St Angelo on the Island of Malta, he became Malta’s most wanted fugitive. He was one of the world’s greatest artists and a Knight of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, Rhodes, and Malta. Ironically, his arrival on the island some fourteen months earlier was also that of a disgraced fugitive, of a person who was trying to rebuild his career and social standing through an impressive network of protectors.

He had escaped from Papal Rome after murdering Ranuccio Tomassoni and surprisingly deciding to go South rather than North. In doing so, he also shaped the character of South Italian early Seicento painting. Afterwards, he sought to try his fortune with the Knights of Malta. The artist’s search for new patrons and protectors, his patrons’ desire to have him in their service and the misdemeanors of his lifestyle all impinged on the character and influence of his art. The story of ‘Late Caravaggio’ is that of a fugitive who produced some of the most powerful pictures of the entire century and, indeed, of the entire story of art. He was constantly on the move and, in many instances, looking over his shoulder. This movement, conditioned by the artist’s fast-paced lifestyle, brought about the fast spread of Caravaggism in the central Mediterranean (South Italy, Sicily and Malta). Caravaggism is the stylistic umbrella of works influenced by Caravaggio.

“Long hours in taverns, brawls, blasphemy, gaming, the colourful aspects of street life, and consorting with prostitutes…”

Caravaggio’s story is filled with powerful patrons who sought to protect him despite knowing that he was a fugitive and that protection could lead to diplomatic consequences. It happened in Naples, Malta, Syracuse, Messina, Palermo, and Naples. Wherever he went, the artist was honoured and protected. Patrons were interested in securing his brush rather than justice.

The artist first arrived in Malta in mid-July 1607, starting an exciting fifteen-month-long Maltese period. In this time Caravaggio, still yearning for Rome, produced outstanding masterpieces only seen by a handful of the great artists. The Knights of Malta honoured his virtuosity and elected him Cavaliere in July 1608. At his first opportunity, the artist proudly signed his name as Fra [Knight] Michael Angelo, painted in the blood oozing from Saint John’s head in the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist painted for the Confraternita della Misericordia’s Oratory of the Decollato in Valletta.

As a Knight of Magistral Obedience, Caravaggio’s social life took on the entirely new dimension of chivalry; he was now bound by obedience, respect for his superiors, and by the strict observance of the Statutes of the Order. Long hours in taverns, brawls, blasphemy, gaming, the colourful aspects of street life, and consorting with prostitutes were to become a thing of the past. He was now obliged to be obedient and decorous in his demeanour.

But Valletta was a cosmopolitan city and temptations were around every corner. It was also a violent city, full of young nobles from various langues, arrogant and difficult to contain. Duels and violence were the order of the day. For a man of such a tumultuous nature as Caravaggio, Malta was a dangerous place. The artist’s turbulent nature could not be contained for too long. His chivalry was disgraced barely four weeks after being knighted. Recent archival research refers to Caravaggio’s involvement in a brawl. In Valletta, on the night of 18 August 1608, a fight broke out in an organist’s house. The organist was from the Conventual Church of St John. The fight involved seven Italian knights and an illegal pistol which was fired.

The Organist’s front door was smashed and the knight, Fra Giovanni Rodomonte Roero, Conte della Vezza di Asti, was seriously wounded. The Venerable Council was immediately notified. An investigation was set up the following day. On 27 August 1608, Caravaggio and his companion Fra Giovanni Pietro de Ponte were identified and detained in Fort St Angelo. Caravaggio escaped soon afterwards.

“Were the Knights responsible for his death?”

Caravaggio has been studied inside out, and in some cases even turned upside down. At the University of Malta’s History of Art Department a programme has been set up just to concentrate on Caravaggio. Over the past ten years, Caravaggio’s 400th anniversary has been celebrated in one form or another. Despite the public successes that the name carried, no one single exhibition (and publication) can be considered to have satisfied all scholars, even though some were obviously much more valid than others.

The speed of research on the artist is fast and keeps on growing, but this Caravaggio craze has taken research off on tangents. A vast plethora of opinions, attributions, and judgments has split Caravaggio studies and many new issues have surfaced. Many questions about Caravaggio’s life and art have been answered, with scientific tools helping to solve problems of attributions and dating. Most major pictures now have a documented story behind them.

Over the past decade, Caravaggio’s late years have come under intense study revealing many important findings. However, several questions remain unanswered. What are the precise reasons why the artist came to Malta? Who directed him towards the island? Why did the Knights support a full Papal pardon? What happened on his eventual return to Rome? Were the Knights responsible for his death? These subjects are still being debated.

How Central Mediterranean Regional Caravaggism was ignored or excluded in major exhibitions and publications is another concern. Caravaggism is not a unified movement. There are important regional differences in Caravaggio’s influence

on artists.

When Caravaggio died prematurely in 1610, he had not set foot again in Rome. In Rome, his followers’ work had rooted itself strongly and had become so established that his death at Porto Ercole did not affect their style. Roman Caravaggism became the ‘mainstream’ type of Caravaggism, but the artist’s movements outside Rome, specifically in Naples, Malta, and Sicily had established other regional styles within the wider context of Caravaggism. These regional styles led to important and unique works of art.

Find out more:

– ‘Frater Michael Angelus in tumultu: the cause of Caravaggio’s imprisonment in Malta’, in The Burlington Magazine, CLXIV, April 2002

– ‘Riflessioni su la Malta di Caravaggio’, in Paragone Arte, 37-38, 2002

– ‘In Memoria Principis: Dying Well in the Late Baroque’ in Journal of Baroque Studies, Vol. 1 No.3, International Institute for Baroque Studies, 2003

– with David Stone, ‘Caravaggio in bianco e nero: arte, cavalierato e l’ordine di malta (1607-1608)’ in Caravaggio L’Ultimo Tempo 1606-1610, Electa Napoli 2004

– ‘Due persone a lui ben viste: The identity of Caravaggio’s companion for the prospective Knighthood of Magistral Obedience’ in The Burlington Magazine, CLXVII, January 2005

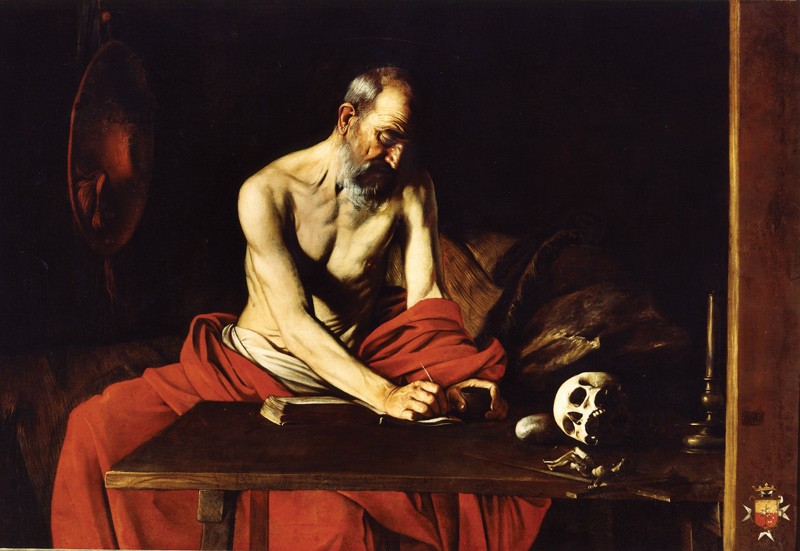

– with David Stone, ‘Malaspina, Malta, and Caravaggio’s ‘St Jerome’, in Paragone Arte, 2005

– Cat. Entries in Vittorio Sgarbi (ed) Caravaggio, Skira (Milan), 2005

– (with David Stone), Caravaggio: Art, Knighthood and Malta, Midsea Books, 2006

– ‘Caravaggio and Realism in Malta’ in Caravaggio and Paintings of Realism in Malta, Foundation of St John’s Co-Cathedral, 2007

– ‘Caravaggio, the Confraternità della Misericordia, and the original context of the Oratory of the Decollato in Valletta’ in The Burlington Magazine CXLIX, November 2007

– Baroque Painting in Malta, Midsea Books, 2009

– ‘Caravaggio en la encrucijada’, in ARS, V.3, N.7, Madrid, 2010

Comments are closed for this article!