If our mutual friend Bread could pass a global decree I believe it would include the mandatory separation between dining and politics. It would absolutely prohibit political discussions when consuming bread. Even if politics is your favorite topic, from its cheap slogans and broken promises, it’s still not a good idea to discuss with your friends while enjoying a soft loaf. It brings back painful memories of a controversial time in Bread’s life–a time when it felt used, helpless, like a puppet in the hands of manipulative elites.

You can find the first part of our Ancient History of Bread series here.

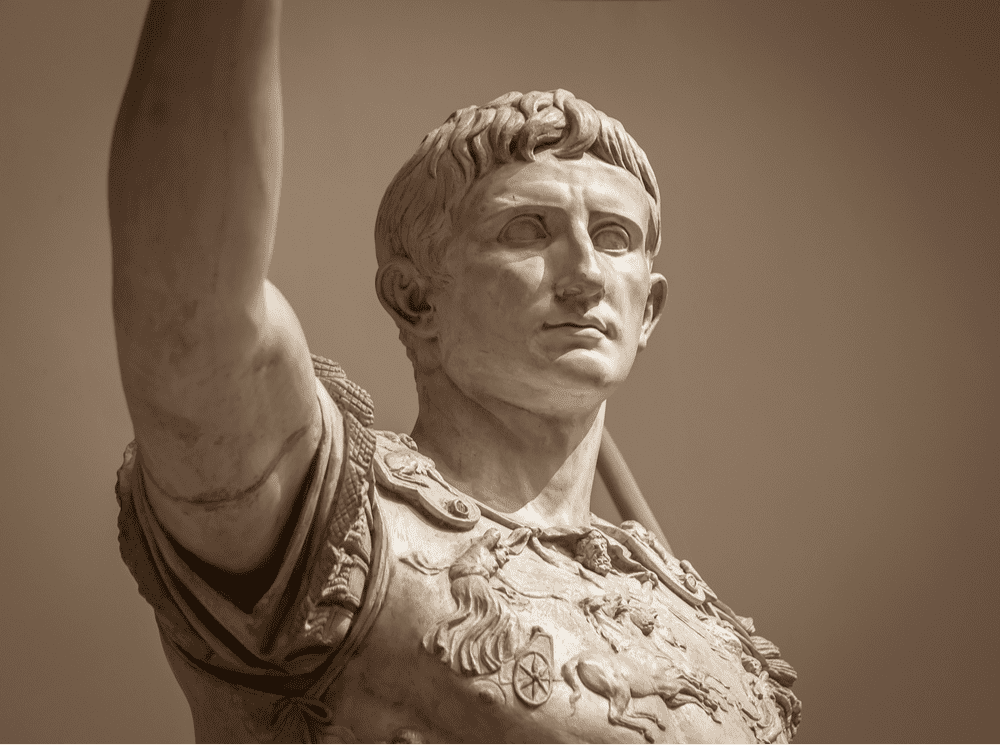

Bread suffered exploitation at various times in different places; however, the most resounding example of its extensive politicization in ancient history occurred in the Roman Empire. You might be familiar with the metonymic Panem et circenses (Bread and circuses) coined by the satirical poet Juvenal. The expression was intended as a critique of the small-mindedness of the lower classes; nevertheless, it indirectly highlighted the strategy employed by Roman public officials to obtain and preserve consensus. Feeding and distracting the masses was the highway to a successful reign, hence many rulers took it, and never looked back.

Bread and Circuses

The practice of offering doles started with the lex frumentaria in 123 B.C. Through this legislation the Romans would import wheat from their provinces in Africa, Sicily and Sardinia to then distribute it at low prices to the poor. Later on, the wheat was handed out free of charge thanks to an updated version of the law tailored by Clodius. As Jacob reports, populations who benefitted from this dubious gift grew exponentially over the years, from forty thousand people in the year 72 B.C. to two hundred thousand during Julius Caesar’s reign (46-44 B.C.). Throughout this time and afterwards, grain came mostly from one location: Egypt.

The relationship between Rome and Egypt clearly shows the strategic importance that bread came to occupy in Roman politics. Egyptian wheat had been the obsession of many, but after Cleopatra’s death, Augustus made a pivotal move when he decided against the direct annexation of Egypt to the Empire, instead keeping the territory as his personal dominion. This decision led to a drastic change in Roman politics for a number of reasons.

First, Egypt didn’t belong to the Roman Empire, it belonged to Octavian Augustus as an individual. Profits coming from Egypt would be destined to the Emperor’s pockets, and he was free to do what he wanted with it. It was only thanks to the Emperor’s benevolence that the wheat continued being shipped to Rome and handed out to its people. Such charity established a direct link between the Emperor and the poorest individuals in society, strengthening his authority through the gratitude and respect from the disadvantaged. Augustus was smart to protect his most treasured possession; in fact he prohibited Senatorial travel to Egypt so that he could prevent any opposing political faction from causing uprisings in the land of pharaohs.

Second, Egypt made up around one third of the total grain importation to Rome, thus without Egypt, an Emperor could not have fed the army and his needy subjects, two of the most important groups to appease if one wanted stable rule in the Eternal City. This was the reason why many of the most dangerous revolts in this period started from Egypt. Its control became the key variable in making or breaking a ruler. For instance, Vespasian in 69 A.D. blocked a Roman fleet trying to transport grain from Egypt to Rome, asserting that the Roman people would have their wheat only after his election. Rome couldn’t live without grains; therefore, surprise surprise, he was nominated Emperor that same year.

With time the lex frumentaria was once again revised and, under Aurelian (270-275 A.D.), instead of wheat, people began receiving two bread doles each. This revised practice of distributing doles had a dramatic socio-economic impact on the Empire’s future. The right to receive bread doles soon became hereditary, hence unemployment rose. The number of bureaucrats needed to sustain this system also grew causing an increase in public expenditure, meaning Roman provinces were progressively drained of their resources. More importantly, the Romans gradually lost their greatest strengths of pragmatism and military genius. These were suffocated by a relatively easy life. With vast portions of the population being fed directly by the Emperor, Romans were free to dwell in leisure rather than spend time determining how to sustain themselves. Once the Barbarians attacked, the Romans had simply become too weak.

The Art of Baking

The gloomy portrait of such an exploitative and self-destructive phase in Roman history should not outshine objectivity. It must be specified that bread’s introduction in the Empire meant positive improvement for some societal groups. When it was first introduced in Rome, the baking of bread was seen as a task reserved exclusively for stay-at-home females. However, around 172 B.C. the rising figure of the baker started gaining a certain level of esteem. The baker came to be regarded as a creative genius, a true artist. His craft was named ars pistorica (art of baking). Bakeries developed and expanded just like its workers’ role and Rome eventually enjoyed the services of two hundred and sixty bakeries, each presenting more or less the same structural characteristics. A Roman bakery generally had a kneading area, a leavening department and a space designated for grinding grain. Furthermore, a portion of the bakery was dedicated to ovens whose product could be sold in the store area. When the baker’s job started booming, some individuals distinguished themselves by gaining extraordinary connections, wealth, and expertise – all thanks to bread. An example is that of Marcus Virgilius Eurysaces, a freed slave turned baker who lived in the second half of the first century B.C.

Eurysaces was a remarkable man who, using what we would call networking, was able to become the Roman army’s favorite bread supplier. Consequently, he amassed enough wealth to afford a massive tomb for himself and his wife in one of Rome’s main streets, a privilege only the very few richest could afford. The monument proving the baker’s rise and bread’s kind gifts to its workers was so well crafted (and lucky) that it survives to this day in Rome close to the area of Porta Maggiore.

Hopefully, it is now obvious that although Bread has been through a lot, it has retained its generosity. Maybe your doughy friend who’s always with you when you need it and never asks for anything in return deserves some gratitude. Don’t make it weird though, no tears, no shouting, no romantic tracks playing in the background, just a heartfelt “Thanks.” Then, keep up the mindful chewing.

Further Reading

Jacob H.E., (2016). Six thousand years of bread: its Holy and Unholy history. Haruaki Publishing. [Number of people who benefited from grain doles, Augustus’ strategies, Importance of Egypt]

Manetta, C. (2016). ” Our Daily Bread” in Italy: Its Meaning in the Roman Period and Today. Material Culture, 28-43. [Roman bakeries and Eurysaces]

Comments are closed for this article!