Malta has the fastest-growing economy in the EU, yet simultaneously the largest number of soup kitchens. How is such an anomaly possible? Prof. Mario Thomas Vassallo, with guests Rev. Ivan Attard and Prof. Manwel Debono, discusses the Maltese Economy and Labour Market on AGORA.

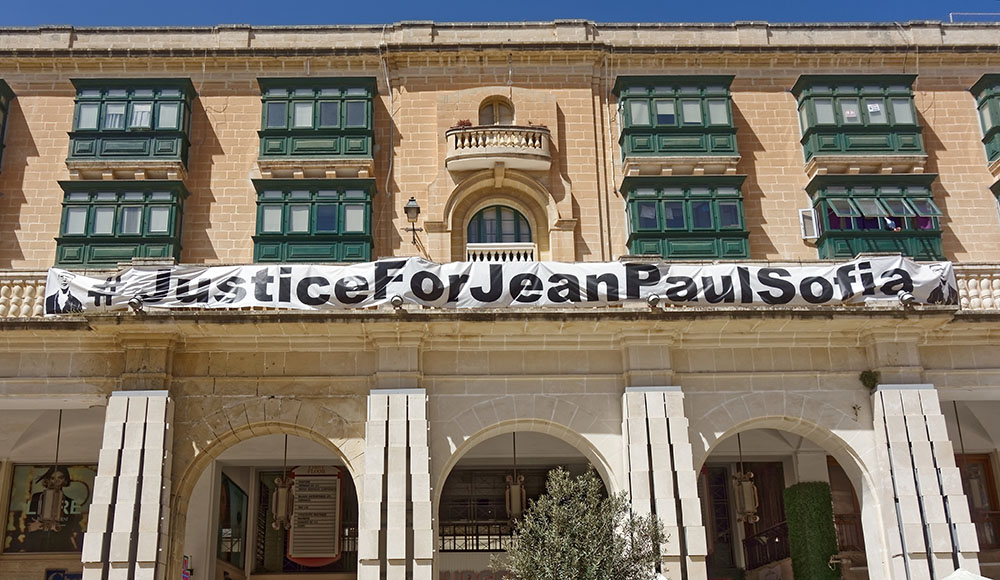

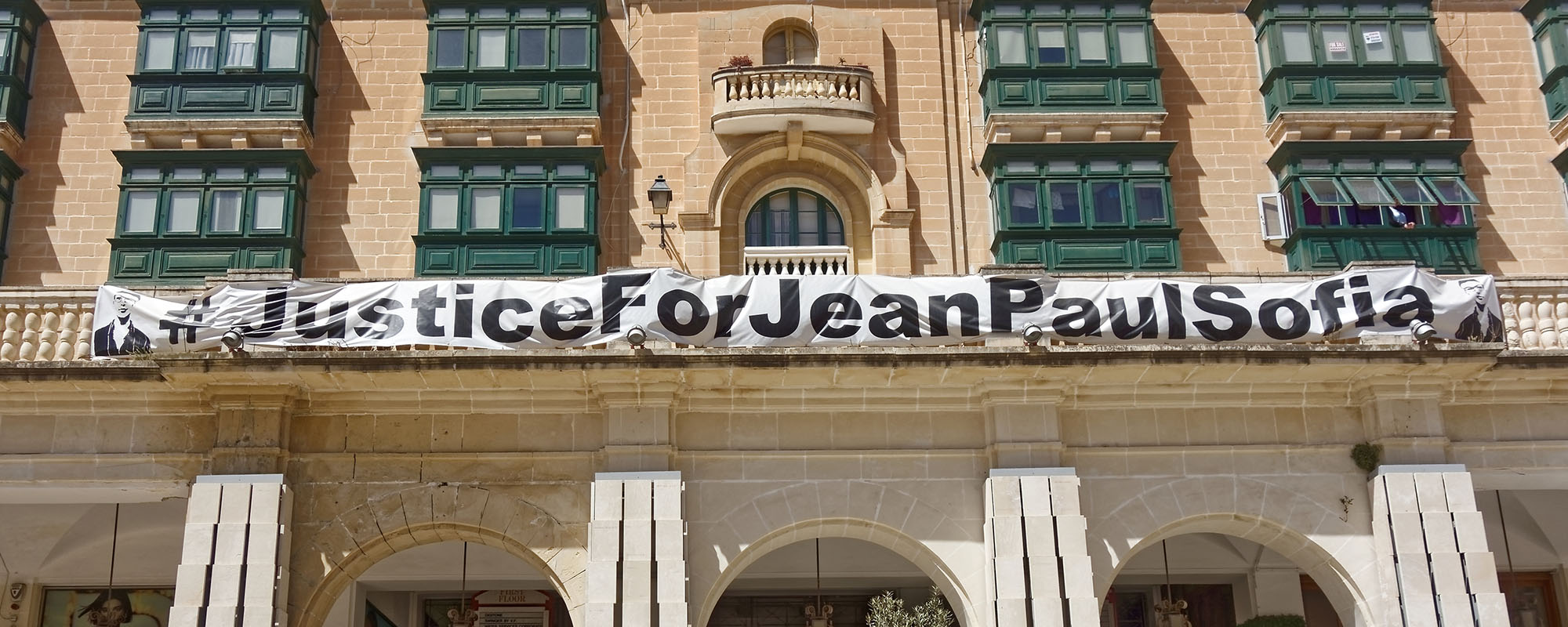

The episode (season 8 episode 11) starts with the backdrop of the Jean-Paul Sofia inquiry, which serves as a tangible, albeit morbid, metaphor for the Maltese economy with its rapid and unmanaged growth that comes at the cost of people’s lives. While the inquiry itself rattled the nation, unfortunately, as Debono (Centre of Labour Studies at UM) points out, many of the issues highlighted were probably already known: incompetencies, half-measures, and improper regulation.

So, while the Maltese economy is growing, it does so at a cost – unsustainable use of natural resources, our well-being, and quality of life. Is this a price we are willing to pay? And what is the point of having a growing economy if that wealth is not justly distributed? As Attard (member of the Anti-Poverty Forum) points out, ‘the economy is growing, unemployment is decreasing, but the purchasing power of individuals is going down’.

Culture of Uwejja

Problems of incompetence are endemic to Malta and can be found in all levels of local society (mind you, this does not in any way justify them). If you’ve lived in Malta for more than a few days, you will have heard the notorious “uwejja” (come on), usually followed by “mhux xorta” (it doesn’t matter/it’s all relative). Locally, we have a nasty aversion to bureaucracy and paperwork, often preferring to cut corners and take shortcuts. However, these are hardly victimless crimes; closing an eye when it comes to inspections or regulations can, and has, resulted in deaths.

Debono points out how you might have skilled carpenters who are, bafflingly, being employed as masons, for example. However, this is hardly the fault of the workers themselves, who, in many cases, are exploited third-country nationals. We only need to look at the side of the road, where contractors dump their injured employees like garbage, to see this exploitation take place.

Unfortunately, the culture of “uwejja, mhux xorta”, is only a short slip away from the more vulgar “Min ħexa mexa. Min ma ħexiex inħexa” (roughly translated to “Those who cheat, succeed. Those who don’t, get taken advantage of”, as I doubt my editor would allow a more accurate translation). It justifies taking advantage of people and manipulating the system, even glorifying it in some cases. But isn’t there a way to protect workers?

Workers’ Unions

Debono points out that not all industries in Malta have unions. For instance, the construction, igaming, and finances industries do not while traditional occupations like in factories, big banks, and government organisations are generally tied to unions.

In principle, unions have an important role serving as the voice of the worker. While they should stand up for the workers and fight for better conditions, Vassallo mentions how locally you might find unions fighting other unions. Malta has three major workers’ unions: GWU, UHM, and Forum Unions Maltin. Debono illustrates how these unions tend to steal members from each other, leading to situations where unions end up sabotaging one another and focusing on their own interests rather than the interests of the workers.

Despite the growing economy, Attard points out that some people are not earning enough to live and buying property or renting is an enormous feat. In some cases (nurses or teachers), your salary is barely enough to get by, and those with low wages, even if slightly above minimum wage, struggle to keep up. On this, Vassallo refers to the Caritas study on the minimum essential budget for a decent living. Incidentally, THINK also discussed this in our article on Food Security in Malta.

Put into perspective, a family of two adults and two children, in 2023, spent €719.50 a month on food, while just a year before, they would have spent €698.80 a month. While medicine and healthcare cost €32.37 a month in 2023, in 2022 it cost €29.60 a month. Just a reminder that the minimum monthly wage in Malta is €924.63 before tax. Even with both parents working, covering basic necessities and rent is challenging. Not to mention that being unable to save money leaves many vulnerable to unexpected expenses, such as a broken appliance or health complication. And this is just to scrape by, we’re not talking about things like vacations or indulgences.

Leaders have somehow convinced us that the only way for the local economy to grow is by having many low-paid workers (often in the form of third-country nationals). Yet, these people need to live, send their children to school, and use healthcare services. Authorities need to think about these aspects as well – after all, workers are not mindless drones. This has led to a vicious cycle with foreigners. You need workers for construction, they need someplace to live, so more flats are built. These flats need to be filled quickly, so they are built haphazardly, once again the “uwejja, mhux xorta” mentality. Unfortunately, this mentality leads to dangerous working environments, something the Jean-Paul Sofia inquiry highlighted. Not to mention that the resulting properties can be used as an easy way to launder money, Debono suggests. While the government has committed to implementing the 39 recommendations, how many have actually been implemented so far?

Regulatory Bodies

Regulatory bodies are supposed to ensure that our working environments are up to code. Yet following the inquiry, Debono notes how, despite having numerous regulatory bodies, it is not clear where one’s responsibility begins and ends. In fact, he points out how this even extends to government ministries. To show this, Debono leaves the listener to reflect on the absurdity of having three ministers inaugurate a new road. Indeed, what is the point?

There is a certain apathy tied to inspections and enforcing laws, a disregard for discipline and rules. Attard observes how if regulations are seen as oppressive, then that will lead to people trying to avoid them. However, we need to show the value behind these regulations to encourage people to follow them. For example, seatbelts. I wear a seatbelt not because I’m afraid of getting a ticket, but because I believe it will help save my life.

Salary and the Economy

Despite all this, it is often touted egomaniacally (by puffed-up politicians) that the Maltese economy is the envy of the world. However, Attard points out that there is a cost for this economic growth; increased frustration, aggression, as well as many young people leaving the country. The problem is not the desire to make money, Attard says, but the insatiable appetite for making money.

Leaders regularly laud the need to increase the GDP, but the benefits of an increased GDP do not affect everyone equally. Sure, there are more luxurious cars on the roads and more villas, but is the wealth reaching everyone?

Take the average worker today and examine the way they used to live a decade ago; has their life improved, remained the same, or gotten worse? If a few years ago, you could live in a house with a small garden, maybe even a garage, and now, to keep up with costs, you’ve sold the house and turned it into a block of flats, with neighbours above and next to you, and no garden. Is that really an improvement? Sure, you might have more money, but you’ve lost many other valuable things.

Vassallo ends with an interesting question, ‘Do people want discipline?’ Our disregard for discipline has become part of the Maltese mentality. Like the problems of hard-headed incompetence and apathy, these need to be overcome. People need to shoulder responsibility. Policymakers need to shoulder their responsibility. We used to say it would take a death for change to be made. Recent history has shown us that even that isn’t enough.

AGORA is a political talk show broadcast on Campus 103.7 every Saturday morning between October and June during which it discusses current affairs with local experts to engage with public opinion in a rational and well-informed manner. AGORA is also available on demand online. The programme is hosted in Maltese.

Comments are closed for this article!