Cassi Camilleri goes on a rollercoaster ride into the relationship between the Humanities and film with Prof. Gloria Lauri-Lucente and Dr Fabrizio Foni. Together, they unpack the debate on film adaptation and points of origin.

With Oscar music still ringing in my ears, I sit down to write this article. At the 90th Academy Awards just passed, The Shape of Water was embraced and celebrated, giving me great joy.

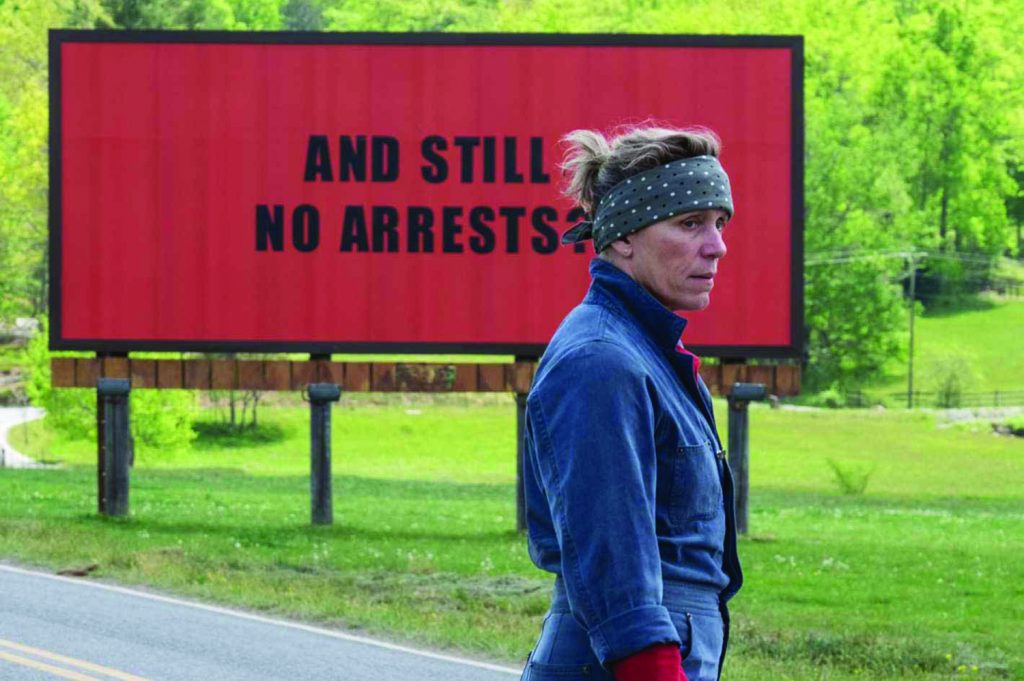

Every year, this celebration of film makes me think and reflect on what kind of productions are being made and shown. So-called ‘original films’ like The Shape of Water, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri and Lady Bird are making waves this year, but my attention is also entertained by the steady stream of adaptations: the behemoth that is the Marvel Cinematic Universe and all of its moving parts, the weird and wonderful The Disaster Artist, Call Me by Your Name… hell, even the latest iteration of Jumanji.

Adaptation in film is a strange beast. Production houses favour it because of the pre-existing audience that comes with it. Fans of the original work are either thrilled to see their precious stories reimagined, or filled with heavy dread for the very same reason. Critics, professional or otherwise, share similar sentiments.

When the film is finally unleashed onto the world, comparison and critique follow close behind. The now-clichéd quip—‘the book was better’—has to be uttered by someone at the cinema within two minutes of the credits rolling lest the universe should implode. All of this brings forth a plethora of questions: What is adaptation and what isn’t? What happens to a text when it is adapted? What is the role of adapted works in art and film?

To answer these questions, I sat down with two of the University of Malta’s researchers in the matter; Prof. Gloria Lauri-Lucente and Dr Fabrizio Foni.

The merits of media

The duo hail from very different backgrounds. Lauri-Lucente, is a lover of the Humanities in all its shapes and forms. In fact, she developed two programmes focused on the intersection of film, literature, and the visual arts; the first is the Master’s in Literary Tradition and Popular Culture, the second is the MA in Film Studies. Foni meanwhile is a cinephile and comic book nut in equal measure.

Both are walking repositories of knowledge that, not so long ago, was looked down upon, sneered at by scholars and academics the world over.

Telling me about the very similar inceptions of film and comics, Foni notes how in their infancy, ‘Both were very neglected media.’ Lauri-Lucente nods in agreement: ‘They were both considered inferior relatives,’ she says. ‘But it took a longer time to acknowledge comics as an art form,’ Foni continues. Even now, however, with comics being widely accepted in the art world, the road is still treacherous. ‘Some scholars are almost afraid of using the term ‘comics’ to actually describe comics. You now have terms like ‘graphic novel’, ‘sequential art’ and so on and so forth. But there is nothing wrong in calling them comics. Even if cinema today is digital, a film is called a film because of the ‘stuff’, the material, from which it was originally made. I think that we cannot focus only on those graphic novels which are considered as an art form because a great novelist one day woke up and decided to script write a graphic novel.’

Both are walking repositories of knowledge that was not so long ago looked down upon, sneered at by scholars and academics the world over.

This explains something about the derision that adaptations experience. Newer art forms cannot hope to be judged with the same respect as their more traditional counterparts. How can a film ever compete with a book? How can graphic design ever be ‘as good as’ painting?

Half-baked deals

When it comes to adaptations, the two researchers have their fingers in many different pies. ‘We’re interested in adaptations, with the term very broadly construed,’ says Lauri-Lucente, ‘Literary texts metamorphosed into cinematic ones, cinematic texts that inspire literary texts. Comics. Paintings. Design—we’re interested in the metamorphic nature of adaptations. How a text is transformed and takes on an entirely new shape.’ The debate that really has them talking is the notion that in adaptation, the point of origin disappears entirely. ‘Both of us, in our different ways and in varying degrees, seriously question the concept that origins can vanish and no longer be traced,’ says Lauri-Lucente.

What happens to the story when it moves from one context to another? When it shifts, spatially and temporally? ‘Despite all the changes, despite all the permutations, the spectre of the original will still linger on, and haunt what comes after it,’ Lauri-Lucente says.

‘If you cannot trace back the source, it is not adaptation,’ Foni notes. And yet, despite the belief in origins, quoting Fredric Jameson, Lauri-Lucente says that in an adaptation, filmmakers can actually breathe an entirely different spirit into their films.

While acknowledging the importance of differences between the inspiring text and its filmic adaptation, the duo also quickly clarify that ‘fidelity’ to the original work is not what they seek. Or rather, fidelity should not be an evaluative measure. While film is sometimes erroneously considered ‘less complex’ than a literary work, this is only because of the perceived immediacy, says Lauri-Lucente.

‘We do not see everything in the frame. It can evoke images that lie outside it… the hors-champs,’ she says, quoting Deleuze. The questions a film can raise are as numerous as they are complex: What lies beyond the screen? What are the sound strategies deployed? How do they clash with the image? Just think about the way sound and image are used in the famous shower sequence in Psycho, the grating sounds accompanied by the rapid intercutting of shots as the knife is brought down onto Marion Crane’s body. ‘Even the most lavished, stylised mise-en-scène of such heritage films as Howards End, A Room with a View, and Where Angels Fear to Tread, all inspired by E.M. Forster’s novels, harbour inner turmoil and conflict below their glossy surface. Viewers should look beyond and beneath what they immediately see,’ Lauri-Lucente says.

In a world where media practically engulfs us, it is easy to be lost in that forest, unable to see the wood for the trees and work through it.

This is where the importance of an overarching perspective comes in, one that is open to intertextual influences and contaminations, while keeping in mind the specificity of cinema as a distinct art form.

‘Yes, with cinema, we need to understand its workings and its language—we have to be knowledgeable about the subject—but we need to keep our view as wide as possible when discussing cinema and its relationship with the visual arts, as well as all the other art forms. How can you discuss Antonioni’s Red Desert without also discussing the paintings by Antonio Burri or Giorgio Morandi? How can Freud’s influence on Fellini’s Otto e mezzo be overlooked?’ questions Lauri-Lucente. ‘We have to be cross-eyed scholars,’ laughs Foni, ‘We keep an eye on one track, but we also need to keep an eye on countless others. If you cut off a thread, the whole spider web is destroyed.’

We have to be more holistic in the way we look at the artwork. Taking into consideration what informs the product. This is the mantra which permeates their teachings. The two colleagues express their efforts to get students to immerse themselves as much as possible in any kind of art. They also worry about the trend that young people seem to be surrounded by art, and yet consuming less and less of it at the same time. ‘What scares me the most is the fact that some students, despite how easy it is to find things these days, refrain from searching,’ notes Lauri-Lucente, ‘Sometimes tending to stick to the mainstream.’

In a world where media practically engulfs us, it is easy to be lost in that forest, unable to see the wood for the trees and work through it.

Reflections

When looking at different art forms, comparison is necessary. The need to question is essential. ‘One cannot refrain from a comparative approach,’ says Foni. ‘I was harshly criticised by some Italian scholars, as most of my published work has aimed to challenge the denial of the existence of an Italian fantastic literature geared towards the broadest possible audience, which offered a type of fantastic analogous to that of pulp magazines, dime novels and penny dreadfuls. This is the case of many short stories and novels published by popular magazines such as La Domenica del Corriere and Giornale Illustrato dei Viaggi.’

But it did exist, and was quite successful. ‘It’s a lowbrow kind of fiction,’ he adds, ‘but the run of these publications is amazing. They were immensely popular. They were anticipating cinematic language, motions, trends, philosophical issues.’ This thought brought the conversation back to perception and elitism in art which seems to be common, if not prevalent.

When I ask why they choose to dive into such dangerous waters, Lauri-Lucente has a revealing answer: ‘Perhaps we’re masochists.’ She laughs and then goes on, ‘Why do we ask all these questions? Well, it’s the only way you can breathe. It provides us with oxygen. I wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I didn’t.’ Invoking the world of Blade Runner 2049, she says, ‘I would not like to live in that type of ambience where everything becomes mechanical. Where there is no place for the interaction of ideas. It would be a very dismal, colourless world, wouldn’t it?’

For information on the MA in Literary Tradition and Popular Culture and the MA in Film Studies, offered by the Faculty of Arts (UM), please contact programme coordinator Prof Gloria Lauri-Lucente here: gloria.lauri-lucente@um.edu.mt

Comments are closed for this article!