Lara Sammut is finding answers to a long-standing challenge in the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department at Mater Dei Hospital. Threatened miscarriage is a poorly understood condition that can lead to pregnancy loss, yet there is little data in Malta to help guide treatments and reassure families. Sammut’s research promises to change that.

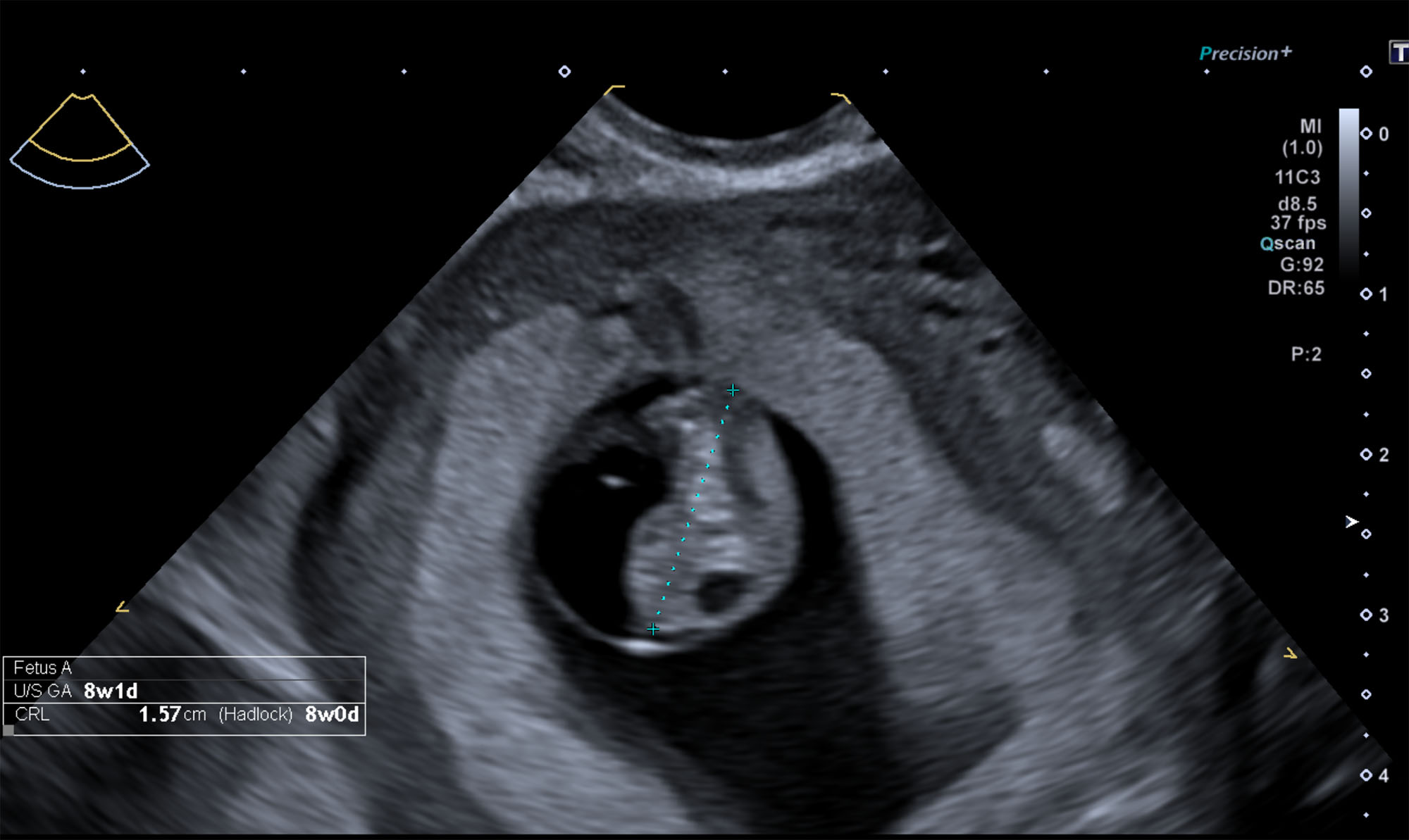

Pregnancy can be a time of great joy but also uncertainty, with many factors weighing in on the normal development of a baby. Ultrasounds are a window into the womb, allowing parents and medical professionals to view and assess the health of the baby.

Ultrasounds are a crucial element of prenatal care, helping to detect early pregnancy complications or anomalies in the baby’s development. However, there are certain conditions that leave families and healthcare providers with more questions than answers. One of these conditions is known as threatened miscarriage.

Bleeding Out

A pregnant person going through a threatened miscarriage presents with vaginal bleeding during gestation, which is never a good sign, regardless of whether it is light bleeding or heavy bleeding. The embryo (the technical name given during the first nine weeks of gestation) or foetus (the technical name given to the developing body until birth) is alive, the pregnant person is bleeding, yet the cervix is closed.

In the best-case scenario, the bleeding resolves by itself and the pregnancy progresses normally. Yet, even if the bleeding stops, it could relate to other complications during pregnancy or delivery. For example, the placenta may separate from the uterus during gestation, the foetus may not grow as expected, or water may break before labour and then lead to premature birth. In the worst-case scenario, the parent may lose the baby.

Threatened miscarriage usually occurs before 20 weeks of pregnancy, yet it is most common in the first trimester (up until the 13th week of pregnancy). Besides bleeding, pregnant people can also present with abdominal pain, pelvic pressure or lower back pain. It can be caused by a myriad of factors, most often impossible to control, from chromosomal problems in the embryo or foetus, to vaginal or uterine infections or trauma. Risk factors may include lifestyle habits, diet, smoking, alcohol, access to health care, and previous health conditions like diabetes.

Doctor’s Orders

Lara Sammut is a radiographer at Mater Dei Hospital. With a Master’s in foetal anomaly ultrasound screening, she has – for the past 13 years – performed ultrasounds on pregnant people at the Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Ob/Gyn) Department. Sammut is also a resident academic at UM’s Department of Radiography and an assistant lecturer, mentoring undergraduate and postgraduate students in Ob/Gyn ultrasound.

When a pregnant person visits the Ob/Gyn department for vaginal bleeding, Sammut explains that the first step is to do an ultrasound to detect what may be causing the signs and symptoms. For example, ectopic pregnancies (when an embryo attaches and starts developing outside of the uterus) also present with similar symptoms at an early gestational age. An ultrasound ensures the location of the pregnancy inside the uterus and rules out a different diagnosis.

Besides this, Sammut also checks the foetus’ heartbeat to confirm the viability of the pregnancy. In a threatened miscarriage, the pregnancy is viable at the time of examination, but due to the bleeding, the pregnancy may be lost later. If nothing is revealed at this point, Sammut then looks for blood clots and other explanations for the bleeding.

If still nothing is detected on the ultrasound, all the hospital can offer is some medication, usually progesterone, to try to stop the bleeding. According to Sammut, in this situation, the person would be sent home and asked to return for an ultrasound in a week or so.

More Data, Please

Besides not knowing what is causing this bleeding, medical teams do not have enough information about threatened miscarriage to provide an accurate assessment of the likelihood of miscarriage. The Directorate of Health Information and Research only collects data after 22 weeks of gestation, leaving no information on the number of pregnant people experiencing threatened miscarriage in Malta, their symptoms, course of treatment, or their outcomes. Families are thus left restless, with no answers or prognosis.

Sammut was not satisfied with this lack of answers. To address the gap in local knowledge, the researcher and academic has started a PhD to collect data on Maltese cases of threatened miscarriage during the first trimester of gestation. With this data, Sammut has created a model that predicts with 93% accuracy the probability of a pregnancy to carry to full term after a threatened miscarriage, which, if implemented clinically, may provide families with much-welcomed answers, more tailored counselling and, hopefully, some peace of mind.

Sammut’s research work is a much-needed study on a condition with a heavy impact on the physical and mental health of pregnant people and their families. THINK will be publishing a thorough deep dive into her PhD study, from the methodology to the results, in Issue 49 at the start of next year.

Sammut leaves the warning, nonetheless, that a limitation of human resources, lack of equipment and the inexistence of an early pregnancy unit at Mater Dei Hospital, risk the implementation of the best practices for healthy early-stage pregnancies.

Further Reading

Mouri, M., Hall, H., & Rupp, T. J. (2024). Threatened miscarriage. StatPearls.

Sammut, L., Bezzina, P., Gibbs, V., & Calleja Agius, J. (2024). Assessing the predictive value of first trimester ultrasound and biochemical markers in miscarriage: A scoping review. Radiography, 30(5), 1368-1375.

Sammut, L., Bezzina, P., Gibbs, V., Muscat Baron, Y., & Calleja Agius, J. (2024). The prevalence of threatened miscarriage in Malta. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology: X, 24, 100353.

Comments are closed for this article!