From the perspective of a student and an academic, how can ChatGPT be used in academia? Nathanael Schembri explores how the AI could be used to aid in assessments as well as scholarly work; such as in writing dissertations and research papers.

Like many people, when I heard about the new ChatGPT AI I wanted to test it out for myself. Around the same time, I spoke with Professor Patrick J. Schembri (Professor of Biology, Faculty of Science, UM) who expressed his concerns on whether this AI was capable of answering assessment questions and therefore could potentially be used by students for such. Armed with my knowledge and training as a science student, and Schembri’s professional experience and knowledge of assessment procedures, we set out to test ChatGPT’s strengths and limitations in academic situations.

Essay Questions

To start off with, we gave the AI some questions from past biology examination papers, divided into 3 categories: 1) essay questions; 2) simple question and answer; and 3) analysis and interpretation of data. Hardly surprising, ChatGPT was able to answer essay questions with ease, outputting essays with clear structure and language, and while the initial outputs were short, the AI could be asked to elaborate further to satisfy the word count. However, the content of those essays was a different story, as upon grading, the AI received a ‘C’, which is not fantastic but is still a passing mark. Schembri expressed that ‘it’s clear [that ChatGPT] has never been to my lectures’ because it did not touch on points or discuss factors that were covered and emphasised in lectures. That being said, the AI could be asked to elaborate further on certain points but that would require a good knowledge of biology and knowledge of the particular points brought up and discussed during lectures. However, it was impossible for me (not being a biologist and never having attended any of Prof. Schembri’s lectures) to achieve a better mark simply on my basic knowledge of biology. The work required extensive research, at which point ChatGPT was much less answering my questions and more aiding me in formulating my thoughts and formating my work in a clear and concise way.

Question and Answer

As for the Q&A style questions, ChatGPT was easily able to correctly answer questions that asked for simple definitions. Answers were very long and included unnecessary information, but any halfway decent student would have been able to trim out the lengthy and irrelevant information. Essentially, it would only be evident that users were being helped by the AI if they simply copy and paste the output without reading it first.

Analysis and Interpretation of Data Questions

When it came to analysis and interpretation of data, things took a downturn and results were unsatisfactory at best, and plain incorrect at worst. Obviously, the AI did not have access to the specific figures and datasets that were part of the question and so I had to transform the data into a form that the AI could read, which took a bit of effort. Initially Schembri and I were both impressed that it was actually able to analyse the data and give an answer, but this was only for simple data (a frequency distribution bar graph); for more complicated datasets, transforming the data into an AI readable format is virtually impossible.

When it came to deducing and interpreting results, the AI was simply incorrect in its answers. The conclusions we reached on ChatGPT is that it faces the issue that all tools do, they are either adequate at a variety of tasks or excellent at a specific one, but not both. The power of ChatGPT is in the former but, as the Schembri noted, it was not able to answer questions in the specific way expected of students as it was not trained with such data. In addition, the reading and interpretation of data with any scientific merit is beyond the scope of ChatGPT, as it was built as a language model. What this basically means is that the programme was taught to recognise patterns in language and replicate them depending on what is most statistically likely for what you ask it.

Scholarly Applications of AI

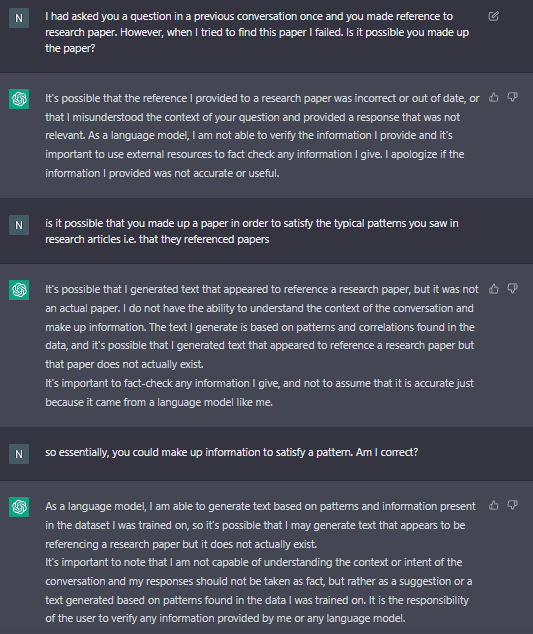

After tackling assessment papers, we then moved on to other possible applications of ChatGPT in academia. As a postgraduate student, I was interested to see if it could help write chapters of my dissertation and so I asked it to write a few paragraphs on heavy metals in Maltese soil. This is where I encountered the largest pitfall of the AI – it made up information. In the output, the programme referred to a paper published in 2010 which I was not familiar with. After scouring Google Scholar, the university’s own library resource manager (HyDi), and the internet in general, I was not able to find such a research paper. Our best guess is that the AI did exactly as it was told and wrote a few paragraphs about heavy metals in Maltese soil, but it did not prioritise being correct. The structure itself was good, as the AI employed the usual language and general sentence and paragraph structure used in academic writing, i.e. it followed the patterns it had in the database that it was trained on. When queried, ChatGPT outputted the following;

As the AI itself put it, any information given by it should not be taken as correct and needs to be verified. This point was further strengthened when I asked it to provide me with a chemical reaction to produce a certain product and its response was outright incorrect. In its defence, after being prompted that the response was wrong, it then provided me with the correct one. Had I not had the background in chemistry to actually know that the first answer was incorrect, however, I would have continued with the wrong information.

Having determined some of the AI’s limitations and applications, Schembri and I moved on to discussing its use in academia. What originally instigated these tests was the ongoing debate in academic circles, local and international, on whether or not a university has to worry about this chatbot being used for cheating in assessments. The answer is both yes and no. Firstly, it can only adequately answer certain types of questions and the student has no guarantee that the answer provided is entirely correct. Another fact that many people seem to have forgotten is a university’s own internal system to prevent cheating. While ChatGPT may be new, students trying to cheat or get away with presenting work that isn’t theirs is not. Even if students are able to get the AI to write their dissertation with correct information, they would have to go through a viva voce examination whereby their deception is almost certainly going to be found out. After all, getting someone to write your dissertation for you is nothing new and there have been lucrative businesses offering that service for decades. This is all independent of the fact that there is already software available to detect the percentage likelihood that a piece of text has been written by an AI, such as Writer.com’s AI Content Detector or OpenAI’s own AI Text Classifier. Therefore, while ChatGPT can be used to cheat, it remains to be seen if the average student would be able to do so effectively.

AIs can be very useful tools for students and researchers, although this is where Schembri and I disagreed. It is my opinion that students or researchers using ChatGPT to improve their level of English, sentence structure, and style, is a positive use of the programme and can only improve the level of academic English in published papers and dissertations. While Schembri agreed to a certain extent, he argued that a good level of English and an appropriate style of writing is still an important part of academic training, and students must demonstrate that they possess an adequate level in order to earn their degree. After all, a degree from a university, apart from ensuring that the graduate has a certain level of knowledge, also certifies that the graduate is competent in other aspects of the subject, which include critical thinking, the ability to address unfamiliar cases, and the ability to communicate.

In my view, ChatGPT is more akin to a calculator or a word processor – it is a tool that helps reduce human error, saves time, and makes life easier, but still requires the user to actually know what they are doing. It is also important to note that the tests carried out and the opinions stated were with regards to STEM subjects, which are characterised by being empirical and data driven. The situation may be different when applying ChatGPT to the arts, languages, and other non-STEM subjects.

In conclusion, while AIs have already proved to be incredibly powerful tools that could revolutionise academia, one should not consider them as the death knell for academia or education in general. AI has the potential to improve the efficiency and quality of education, but the human element will always be important in education as it provides a unique perspective and creativity that AI cannot replicate. Therefore, the integration of AI into academia will serve to aid and improve research and education, not replace them.

The author of this article, Nathanael Schembri, is currently reading for a postgraduate degree in Rural and Environmental Sciences with the Institute of Earth Systems at the University of Malta.

Comments are closed for this article!