You may be surprised that the level of social integration and the number of close relationships a person has is one measure of their life expectancy, but with reports suggesting loneliness is on the rise, are we facing a new epidemic? And are there specific social, demographic, or economic factors that are contributing to this rise? In this article, Chris Styles speaks to Jamie Bonnici from the University of Malta, Faculty for Social Wellbeing, about a 2019 study on the prevalence of loneliness among the Maltese population and if these feelings of isolation are more prevalent in certain demographics, a study which has been replicated recently as well.

Loneliness – It’s More than a Feeling

Do you love being part of the crowd, or do you prefer the company of just a few close friends? The labels introverted and extroverted are a commonly used shorthand to describe how people feel about social situations, but we all need the company of others sometimes. If you describe yourself as having a small appetite, it does not mean you do not need to eat at all. And although you may feel like this comparison is not particularly apt, more and more studies have demonstrated the importance of social interaction on our physical and mental health.

If you have ever felt the pang of missing someone you have not seen in a long time, that pain is not imaginary! Our brains have been wired in such a way that when you feel a sense of being alone, it shares a similar neurological pathway to physical pain, and when you eventually are reunited and you give them a hug (or however you express yourself), your body also reacts physically, by releasing oxytocin and dopamine into your bloodstream, improving your mood and relieving stress. In fact, a person’s social connectivity and the number of close-person relationships they have is one of the key indicators of life expectancy, comparable in importance to the amount of exercise you do or even if you are a smoker or not. Recent research has suggested that the long-term health implications of feeling lonely could have a much greater impact than previously realised – not just for a person’s mental health, with loneliness being linked to anxiety, depression, diminished life satisfaction and overall resilience – but also to a person’s physical health, including increased risk of stroke and heart disease, high blood pressure, and weaker immune systems. Because of this, some researchers are considering loneliness a modern ‘epidemic’.

Unfortunately, it seems that loneliness is on the rise, and although there is some debate within the research community as to exactly what extent, feeling lonely is just an inevitable part of the human condition.

But what about those living on the Maltese Islands, the isolated archipelago in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, home to over 525,000 people (115,449 of which are foreigners)? How lonely is this population, and are there any specific social, demographic, or economic factors that contribute to these feelings of isolation? Well, that is a question that a team of researchers from the Faculty for Social Wellbeing wanted to answer.

Jamie Bonnici was part of the research team (including Prof. Marilyn Clark and led by Prof. Andrew Azzopardi) that orchestrated this study, and in 2019, they conducted a systematic survey of the population of Malta to identify the extent of these feelings of isolation.

Measuring Loneliness – Complex emotions

‘Loneliness has been described by social science researchers as a symptom of other societal issues; the exact reason why someone might experience these feelings is very complicated to understand and there is no one-size-fits-all solution.’

Jamie Bonnici

For an issue with so many complex and personal dimensions, the research team thought it was important to invite academics and representatives from each of the departments at the University of Malta to join a working group, an opportunity to discuss the potential sociological and psychological associations linked to loneliness on the island. From these collaborative sessions, the research team designed a survey protocol which collected data using a bespoke Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) procedure. This survey consisted of questions from the standardised De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, featuring statements such as ‘There is always someone I can talk to about my day-to-day problems’ and ‘I often feel rejected’, where participants could either agree, disagree, or feel neutral about these statements. In addition, questions were included to gather information on each of the participants’ socio-demographic status as follows:

• Age group

• Level of education

• Labour status

• Household composition

• Mortgage status

• Perception of household income

• Subjective physical health

• Subjective coping ability

• Subjective well-being

• Presence of a disability

‘One obstacle to obtaining a clear picture of loneliness is the variation that exists in terms of the research tools used to assess loneliness. This makes it difficult to accurately compare data across countries and time.’ Bonnici explains, ‘This is the first representative study of this kind to be conducted in Malta.’ The socio-demographic criteria the research team chose were based on existing studies that have been done into loneliness, as well as factors that could possibly result in lower feelings of belonging within a community.

The questionnaire was presented in both Maltese and English throughout March of 2019 and gathered information from a random sample of Maltese citizens throughout the island. Featuring respondents aged 11 years and older, the survey was designed so as to ensure that an adequate representation of participants was reached based on gender, age group, and district.

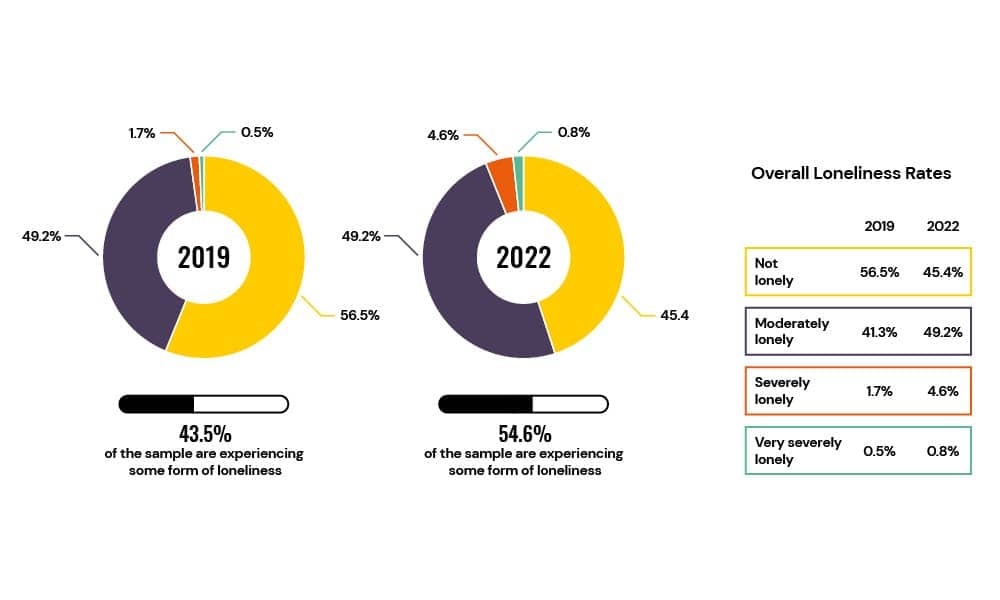

Over the survey period, the research team received responses from 1,009 participants, and of these, 43.5% of respondents reported themselves as experiencing some degree of loneliness (41.3% moderately lonely, 1.7% severely lonely, and 0.5% very severely lonely). When the research team looked more closely at the data, they were able to identify groups in the community who appeared to have less social capital (the ability to form wide networks of relationships within society). These groups included but were not limited to the elderly; those who have limited educational attainment; the unemployed, retired, or otherwise not in employment; those who are widowed, separated, divorced, or married; those who live alone; people who perceive their household income to be low; and those who would rate their physical health as ‘bad’ or identify as disabled.

A recent follow-up study, conducted by the faculty in 2022, compares the data obtained from the 2019 study. The results suggest an increase in loneliness over the past 3 years with 49.2% of respondents feeling moderately lonely (as opposed to 41.3% in 2019), 4.6% feeling severely lonely (1.7% in 2019), and 0.8% feeling very severely lonely (0.5% in 2019).

‘I was surprised to see that loneliness was present in Malta on this scale,’ Bonnici comments, ‘I had always seen the people of Malta as very close-knit and neighbourly.’

Being less lonely – No easy answers

There is no one factor that contributes to a person feeling isolated, but rather a collection of circumstances that have led them to feel disconnected. This unfortunately means that there is no single answer to how to alleviate this epidemic,‘It’s difficult to say whether such impacts can be resolved by simply being more social, since loneliness is a subjective experience: people can have a large group of friends and still feel lonely, particularly if they do not feel that there is someone they can turn to when they need support,’ Bonnici says. ‘For individuals seeking to combat loneliness, whilst there is no one-size-fits-all approach, research has demonstrated benefits of engaging in volunteering activities, as well as possibly speaking to a therapist to address any maladaptive thought patterns which might have developed. Our research has also shown that certain factors may be protective against loneliness, such as furthering one’s education.’

Being alone and loneliness are often considered to mean the same thing, but they are not. You can feel lonely even when you are surrounded by people; loneliness is also a subjective feeling and perhaps a self-fulfilling prophecy somewhat. If you feel lonely, then you are lonely, and if you are feeling lonely you may also lack the confidence to go out of your comfort zone to acquire new connections, creating a loneliness feedback loop.

However, modern life and the social restrictions put into place during the turmoil of the COVID-19 pandemic certainly have not helped the situation. Many of us have found ourselves changed by the situation. Although at the time of writing this article, COVID-19 safeguards have drastically been relaxed, many people are finding it difficult to maintain a healthy work-life balance, finding new societal pressures difficult to deal with, or just struggling to find the time to maintain the social connections they once had. The exact impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had upon our lives is still being unravelled by researchers, with Bonnici and the team at the Faculty for Social Wellbeing recently finalising the data collection for the second round of loneliness research, which may give an indication of any changes that have occurred during the pandemic. Early findings show younger age groups (11 to 19 years) having higher rates of overall loneliness than older age groups

Almost paradoxically, in a world where we can connect with anyone at the push of a button, many of us are lonelier than ever. But there are a few things that we can all do; we can all be aware of this issue and look out for each other. Reach out to friends and family. Awareness of the issue is the key, and if you or someone you care about is suffering but are unsure of what to do, please do get in touch with an organisation such as Malta Together. They are here to help. Other professional support services include kellimni.com; alternatively you can phone the national helpline on 179.

You are not alone!

Further Reading

Tiwari, S.C., 2013. ‘Loneliness: A disease?’. Indian journal of psychiatry, 55(4), p.320.

Cacioppo, J.T. and Patrick, W., 2008. Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. WW Norton & Company.

Beutel, M.E., Klein, E.M., Brähler, E., Reiner, I., Jünger, C., Michal, M., Wiltink, J., Wild, P.S., Münzel, T., Lackner, K.J. and Tibubos, A.N., 2017. Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC psychiatry, 17(1), pp.1-7.

Zebhauser, A., Hofmann‐Xu, L., Baumert, J., Häfner, S., Lacruz, M.E., Emeny, R.T., Döring, A., Grill, E., Huber, D., Peters, A. and Ladwig, K.H., 2014. How much does it hurt to be lonely? Mental and physical differences between older men and women in the KORA‐Age Study. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 29(3), pp.245-252.

Valtorta, N.K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S. and Hanratty, B., 2016. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(13), pp.1009-1016.

Hawkley, L.C. and Cacioppo, J.T., 2010. ‘Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms’. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), pp.218-227.

Hawkley, L.C. and Cacioppo, J.T., 2007. Aging and loneliness: Downhill quickly?. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), pp.187-191.

Comments are closed for this article!