On 21 October 2022, HUMS presented their first event of the new academic year! Four speakers explored ‘forensics’ in a variety of scenarios, from police work and literature to archaeology and medicine. Just in case you missed it, we’ve prepared an article to bring you up to scratch!

The Platform for Humanities, Medicine, and Science (HUMS) was launched in 2012 as a joint initiative by the Faculty of Arts, the Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, and the Faculty of Science at UM. HUMS’ main focus is to promote research that brings together academics from the three founding faculties to establish an interdisciplinary dialogue through regular meetings, seminars, and conferences. Via its activity, the platform aims to encourage interdisciplinary research among undergraduate and postgraduate students by supplying educational material. Additionally, HUMS seeks to collaborate with stakeholders locally and internationally to provide academics with a forum where they can share their latest research, theories, findings, and ideas to raise them onto a joint platform of dialogue.

Forensic Interdisciplinarities

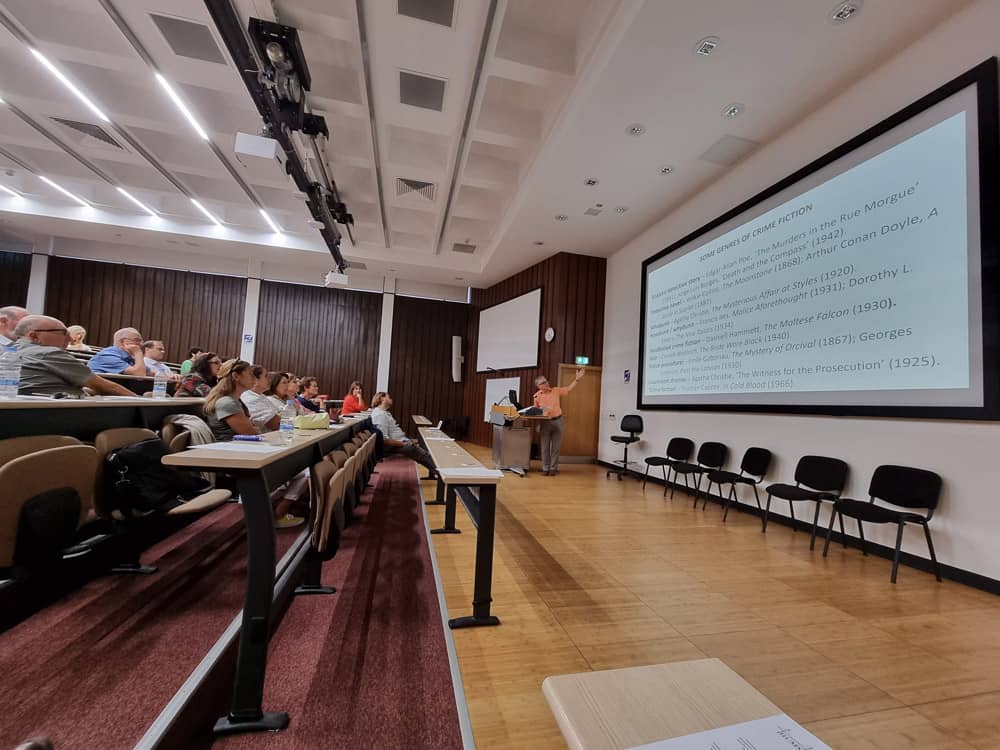

Under the aegis of these mighty aims, HUMS organised a symposium with the central theme of Forensic Interdisciplinarities, focusing on Forensic Medicine, Criminology, Archeology, and Detective fiction on 21 October 2022 at the Arts Lecture Theatre. The symposium, via its speakers, investigated how forensics is represented in different academic fields. The event was hosted by Prof. Clare Vassallo, coordinator of the HUMS Board, who facilitated the discussion between the speakers: Prof. Charles Savona Ventura, who spoke about forensic medicine in pre-19th century Malta; Prof. Saviour Formosa, who elaborated on 3D crime scene reconstruction with a focus on spatial forensics capture to immersion; Emma Richard-Tremeau, who discussed reconstructing the past through pottery; and Prof. Ivan Callus, who explored forensics in early detective fiction.

‘Such activities have been ongoing for 10 years to bring together students and professors of different faculties to connect from an academic and social point of view too,’ Prof. Vassallo said in her introductory speech. ‘Last year, our main theme was “bridges,” which comes as no surprise as the HUMS emblem is a bridge – our utmost focus is to bridge the gap between scientific fields to create synergies, knowledge sharing, and enable joint research.’

This year’s symposium’s main theme of ‘forensic interdisciplinarities’, peeks into the past and follows attempts to reconstruct events and series of actions. With this idea in mind, Prof. Callus (Department of English, Faculty of Arts) set the tone for the symposium as his presentation ‘Forensics in Early Detective Fiction’ ventured into how this academic field has been represented in works of literary art.

Forensics in Early Detective Fiction

‘It may seem that the forensics we have today could not have been present earlier. However, in early detective fiction, forensics gradually starts being represented as we move on with time,’ Prof. Callus said. Early traces of forensics appeared in the Sherlock Holmes works by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Prof. Callus quoted Doyle’s work, which describes in-situ forensics by detective Holmes as described by friend Dr John H. Watson.

‘For twenty minutes or more he continued his researches, measuring with the most exact care the distance between marks which were entirely invisible to me and occasionally applying his tape to the walls in an equally incomprehensible manner. In one place, he gathered up very carefully a little pile of grey dust from the floor and packed it away in an envelope. Finally, he examined with his glass the word upon the wall, going over every letter of it with the most minute exactness. This done, he appeared to be satisfied, for he replaced his tape and his glass in his pocket.’

Prof. Callus reminded the auditorium packed with enthusiastic people that at the beginning of the Holmes story, Dr Watson is intrigued by Sherlock and keeps observing and recording the detective’s vast knowledge, which is a good example of interdisciplinarity. While Doyle’s work may be one of the better known stories, thanks to Sherlock’s character being famous on the screen, literature has long been fascinated with forensics, clearly present in the works of Enid Blyton, Georges Simenon, Edgar Allen Poe, and Agatha Christie – just to mention a few.

‘In the absence of forensics as most commonly understood in present-day usage and practice, early detective fiction appears to have placed in its foreground, instead, other processes and theatres of forensic investigation and procedure,’ Prof. Callus said not long before opening the floor to Prof. Charles Savona Ventura, who spoke about Forensic Medicine in pre-19th century Malta.

Forensic Medicine in pre-19th Century Malta

With detective and investigative fiction gaining popularity in novels and on the screen, people usually think about forensics as a modern field of study. However, Prof. Savona Ventura (Head of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery) presented evidence on forensics dating back to the late 16th century.

Forensic medicine is often described as applying medical and paramedical scientific knowledge to certain branches of both civil and criminal law. Prof. Savona Ventura mentioned two main categories: firstly, clinical forensic medicine, which is the investigation of clinical state assessment in living patients; and secondly, pathological forensic medicine, which is the examination of the deceased to identify the cause of death.

‘Maltese legislation goes back to the 16th century on medical forensics. A 1586 decree, which may be the earliest record of medical forensics, more than once prohibited surgeons from treating lesions produced by weapons and were obliged to report the case to law officers within 24 hours,’ Prof. Savona Ventura said.

In his presentation, the expert laid out numerous recorded court cases throughout Malta’s history, starting from the early 16th century, when some form of clinical or pathological forensic medicine procedures was applied to help the judge make their decision.

‘Forensic medicine before the 19th century was primarily based on clinical features and

postmortem examinations, with a restricted extent of ability to make a definite correct diagnosis. However, during the 19th century, the scope of forensic investigation was quickly augmented by laboratory studies, which significantly increased the scope of diagnoses,’ he concluded.

Reconstructing Past Activity Through Pottery Analysis

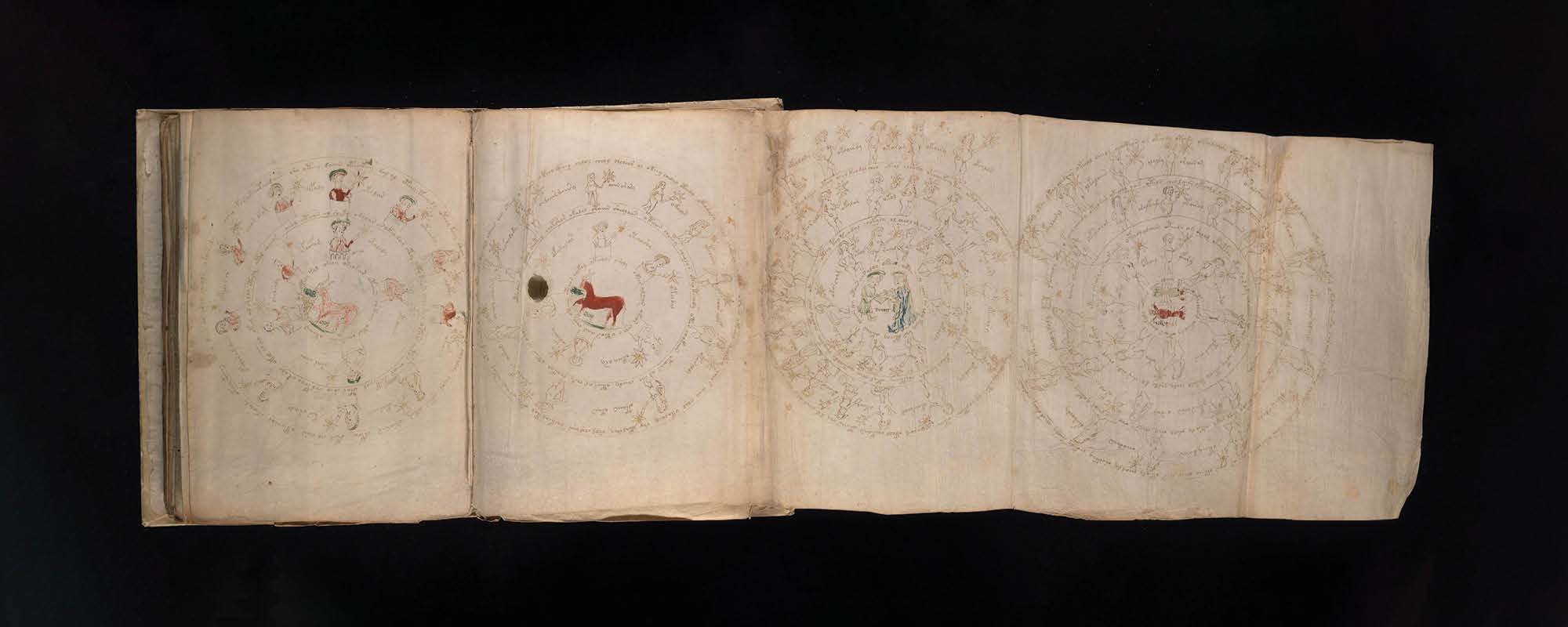

Emma Richard-Tremeau (Research Support Officer, Department of Classics and Archaeology, Faculty of Arts) explored how pottery remains and shards excavated through archeological activity help our species reconstruct past activity. ‘Pottery survives very well in time, which gives us a great chance to study them and try to understand how we can use them to recreate the past. However, as pottery shards come in tens of thousands of pieces, their analyses are laborious and lengthy,’ Richard-Tremeau said.

When archaeologists study excavated shards, they focus on form, surface, manufacture marks, residues, use-wear, content in situ, and material/fabric to understand the function of the pottery item and make assumptions relating to how the users of the pottery may have lived. By studying the residue found inside the shards, for example, research can help determine the function of the pottery. Additionally, understanding where the clay used came from can help experts determine how and where they were made.

All these investigations use forensic techniques. ‘Technological studies, such as looking at the patterns under a microscope to see the fabric, can help us understand how and why the pots were made,’ Richard-Tremeau said. However, she warned of some of the limitations of her field, too. ‘The state of the evidence is important, as if it is affected by degradation, upcycling, fragmentation, or disturbance, reconstructing the pot to make deductions may be more difficult,’ she concluded.

3D Crime Scene Reconstruction

In stark contrast to pottery, Prof. Saviour Formosa (Associate Professor, Department of Criminology, Faculty for Social Wellbeing) presented technology that enables the reconstruction of a crime scene in three dimensions to help support witnesses’ memories. ‘Recreating a crime scene is challenging. We use two main methods – photogrammetry and laser capture – to build a spatial model, which can offer a full-blown coverage of a crime screen in 3D, completely explorable by wearable tech such as virtual reality or augmented reality goggles,’ the professor said.

The technology Prof. Formosa uses for forensics is highly developed. One of the drones he is working with can take off and capture photos to create a point graph and then a mesh to create a three-dimensional map of any terrain, which enables the experts to create the exact three-dimensional time capsule of any scenario.

‘The main problem is that when we have a court case, the magistrate may not be willing to go in situ. But the imaging we can create may help reconstruct the same three-dimensional environment so the magistrate and the judge can have a walk around in the actual crime scene,’ the professor said.

The drone they use can support functions that go beyond crime investigation. For instance, the same drone has been used to create a three-dimensional model of a bay near Għar Lapsi. ‘Before the sun rises, there is already enough light for the cameras to map the underwater area without water-level reflections causing a disturbance; it is possible to look through the water and create a 3D image of the seabed,’ he mentioned.

Further to creating models of terrain, the technology these researchers use can create three-dimensional models of objects or even humans. ‘Taking videos and converting them to photos and creating point clouds is the most efficient way of creating body images in 3D,’ said Prof. Formosa, whose team was involved in scanning former Olympic 400m swimmer Neil Agius, who last year broke the record for the longest non-stop, unassisted swim – a staggering 50-hour tread of 125km from Linosa to Malta.

At the end of the symposium, Prof. Sandro Lanfranco, Associate Professor and Head of the Faculty of Science, thanked the presenting academics as well as interested participants in the audience for their presence. He praised HUMS for its efforts and achievements in bridging the interdisciplinary gap and hinted that many such events will follow.

Author

-

Christian Keszthelyi is an English linguist-turned journalist, writer, PR flack–you name it. He contemplates a lot about life and writes every now and then.

Comments are closed for this article!