Innovative teaching methods can make even the most ancient works feel contemporary

Like the generations of leaves, the lives of mortal men. Now the wind scatters the old leaves across the earth, now the living timber bursts with the new buds and spring comes round again. And so with men: as one generation comes to life, another dies away.

Book VI of The Iliad

‘Like the generations of leaves, the lives of mortal men. Now the wind scatters the old leaves across the earth, now the living timber bursts with the new buds and spring comes round again. And so with men: as one generation comes to life, another dies away.’ – Book VI of The Iliad.

You may be forgiven for thinking that an epic poem composed during the 8th century BCE would have nothing to offer a 21st century audience. But perhaps as evidenced in the quote above, beneath the veneer of heroic battles and tragically fated lovers, Homer’s Iliad ultimately deals with the essence of the human experience. Dr Carmel Serracino, lecturer of Classics at the Department of Classics and Archaeology makes use of engaging teaching methods to bring Homer’s seminal works to a modern audience.

Falling for the Classics

‘I was first bitten by the Classics bug when I was at university myself, reading for an Archeology degree. I didn’t expect to be so immersed in the work, but reading Homer for one study unit is what ultimately pushed me to specialise in Greek and Latin,’ he says, describing his first encounter with Homer’s epic works.

Homer, who is believed to have lived during the 8th century BCE, is still recognised as one of the most influential poets of all time. He is known for his epic poems: the Iliad (set during the ten-year Trojan War) and the Odyssey (which focuses on Odysseus’ ten-year journey home after the fall of Troy). Although we nowadays know these works in their written forms, scholars believe that the works were originally transmitted orally, a performative tradition that ultimately inspired Serracino in his teaching of the work.

Breathing Life into Teaching

Serracino explains that the idea to start teaching the works in a different way was born when one of his students demonstrated exceptional engagement and decided to put up a play inspired by the Iliad during his first year running the course.

‘All the students in the group got involved in the end, and staff were also very happy to participate. The fact that the students engaged with the work so much as a result of this got me thinking about changing the assessment method of my course,’ he says, explaining that the course grading is now split between a creative project and a write-up (worth 60% and 40% respectively). This year, however, Serracino decided to test a different teaching method to try and instil more creativity into the way the lectures are carried out as well.

‘I decided to introduce a variety of activities into the lectures. We had a range of “chair in the middle exercises” for instance, where students took turns to role-play a character from the Iliad as the rest of the class prepared questions and debates for them to address in character.’

Although this method might seem daunting, and though it was unlike any of his own experiences of being taught the classics, Serracino stressed how impressed he was by the level of participation and dedication his students showed.

‘Some of them even dressed up as the characters, and they presented new and surprising interpretations of characters I have been reading about for so many years. Naturally, I found these reactions very encouraging, and I even asked the students to participate in the design of the lectures sometimes.’

Serracino goes on to explain that he felt the interactive nature of the lessons led to the students truly internalising the subjects, and it resulted in some outstanding work in their creative projects, a sentiment which is echoed by the students. In fact, Classics (Hons) student Skye Vassallo took inspiration from the role-playing exercise for her creative project.

Classical Works and Modern Interpretations

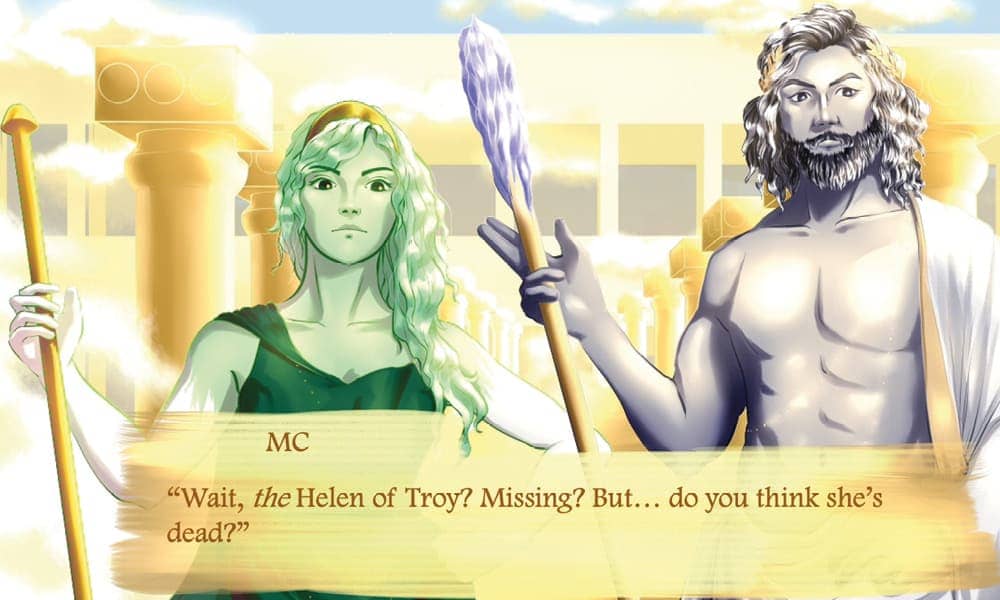

‘For my project, I designed a visual novel game based off the perspective of Helen of Troy: an interactive story where the player experiences various events of the Iliad and also has to make certain decisions along the way, which will produce different outcomes,’ Vassallo explains, adding that the player essentially role-plays as a 21st century student approached by the gods to replace Helen due to her recent mysterious disappearance.

‘The actual project included character designs, the written story, and a playable demonstration of the first chapter,’ she adds.

Vassallo goes on to explain that the inspiration for the plot of her project came from an idea floated by some ancient authors she came across in preparation for the classes, namely Stesichorus, Herodotus, and Euripides. Stesichorus proposed that there was only an image of Helen in Troy, and Herodotus and Euripides wrote about Helen being in Egypt during the Trojan War. These views helped Vassallo to form the theory at the heart of her game: that the woman who resided in Troy was only a phantom Helen, with the real Helen waiting elsewhere.

‘The inspiration for this type of project came from my love for visual novel games. They deliver stories both visually and textually at the same time, while also giving the player the power to change their fate in the game, which felt like the perfect way to bring the Iliad into present-day media,’ she says, adding that the innovative way of teaching ultimately pushed her to realise that she could connect with these monumental works in a fun way and on a deeper level than she had ever imagined.

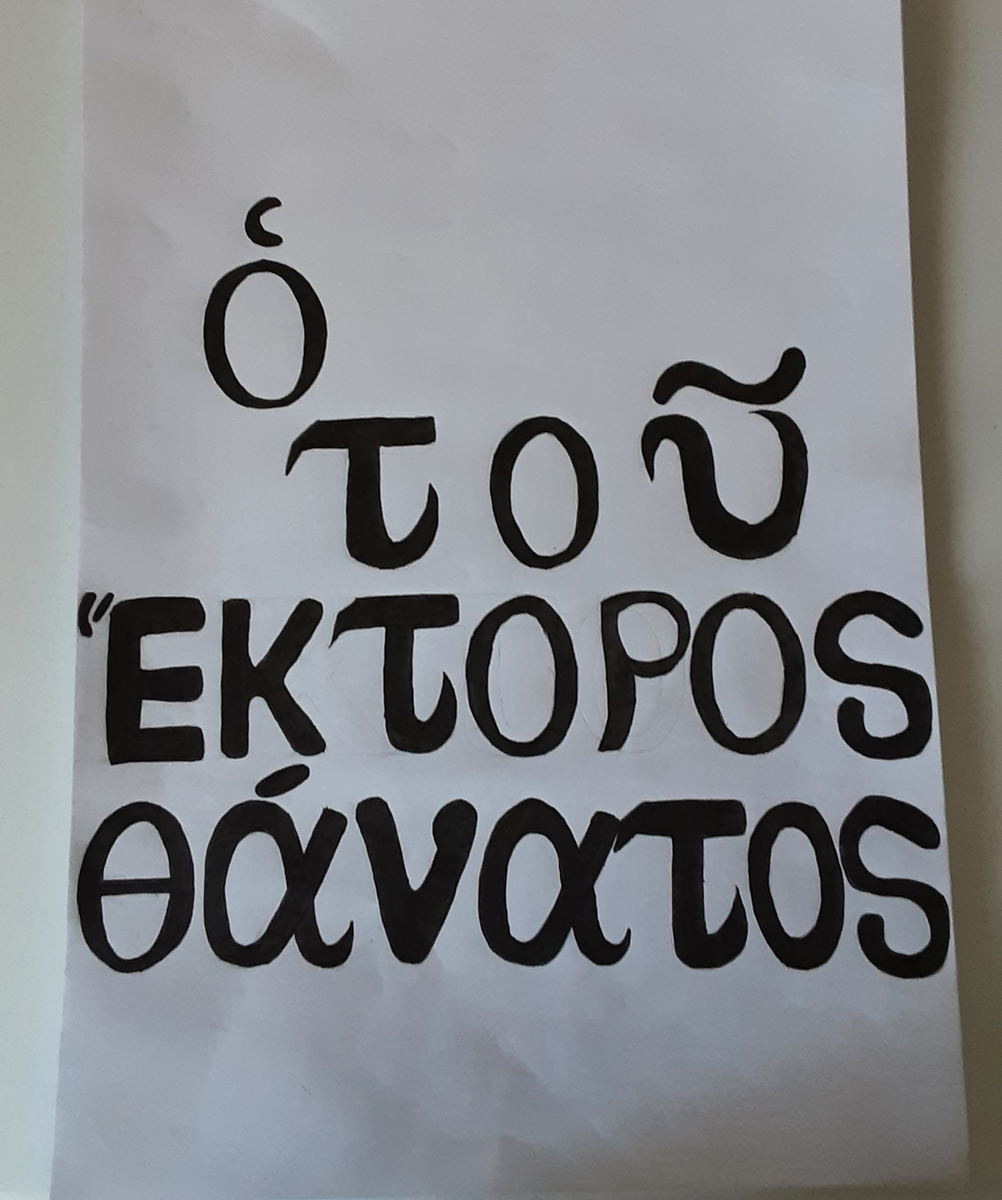

Another student who took inspiration from character appearances was Classics (Hons) student Kayleigh Frostick, whose project is an Ancient Greek abecedarian-style ‘book’ influenced by a mixture of Edward Gorey’s The Gashlycrumb Tinies and Ancient Greek pottery. For the uninitiated, an abecedarian poem is an acrostic poem that spells out the alphabet either word by word or line by line, which gives you an idea of the complexity of this project. If that’s not impressive enough, Frostick even used the Greek alphabet for this task…

‘I corresponded 24 soldiers who met their end within the Iliad to each letter of the alphabet in an overarching poem with accompanying illustrations, serving as a sort of memoir for these fallen soldiers.’ She adds that the process of creating the accompanying illustrations also helped her to reignite her passion for art, and she hopes to continue building on this type of work.

‘Sometime in the future, I would also like to refine this project and perhaps even publish it or others like it one day. A fresh take on classical literature can never go wrong,’ she shrugs.

Bachelor of Humanities student Carmelina Sammut says that the focus on individual characters in the work ultimately helped her to visualise characters that often feel larger than life. ‘I ultimately was drawn to the character of Patroclus, which shaped my final project: an analysis of the friendship between Patroclus and Achilles.’

Sammut goes on to explain that visualising the characters in that way was something that she hoped she could carry on into other subjects and study-units, namely philosophy, which she is currently tackling. ‘It grounds the arguments presented and helps humanise even the most complex philosophers,’ she explains with a laugh.

She adds that although initially she was sceptical about the concept of learning through games and activities, the process has meant that she remembers these characters much more than she expected. ‘This study-unit has given me an urge to do a Classics degree, and this method of teaching has made it feel easy to grasp and study,’ she says.

Similarly Bachelor of Humanities student Mariella Bose also spoke about how surprised she was to discover this new method of teaching. ‘I first attended university in the 70s and I expected a conservative approach to the subject,’ she says. ‘Dr. Serracino’s way of teaching brought us as students together to talk, research, and discuss various aspects of the epic. The lectures were not a one-way street but involved each and every one of us working together. We were made to delve deeper into the psychological and emotional make-up of the heroes and the gods,’ she adds.

In fact, even students who only audited the class without submitting a project sang praises of this teaching method, with 3rd year Classics student Andrew Debono Cauchi telling THINK that the sessions helped shape his personal impression of the epic through his engagement with the literary masterpiece.

‘I hope to continue building on the work we have done during these lectures by employing similar techniques and exercises in my readings of other Classical works too. Moreover, I also wish to read Homer’s Iliad in the original Greek text,’ he added.

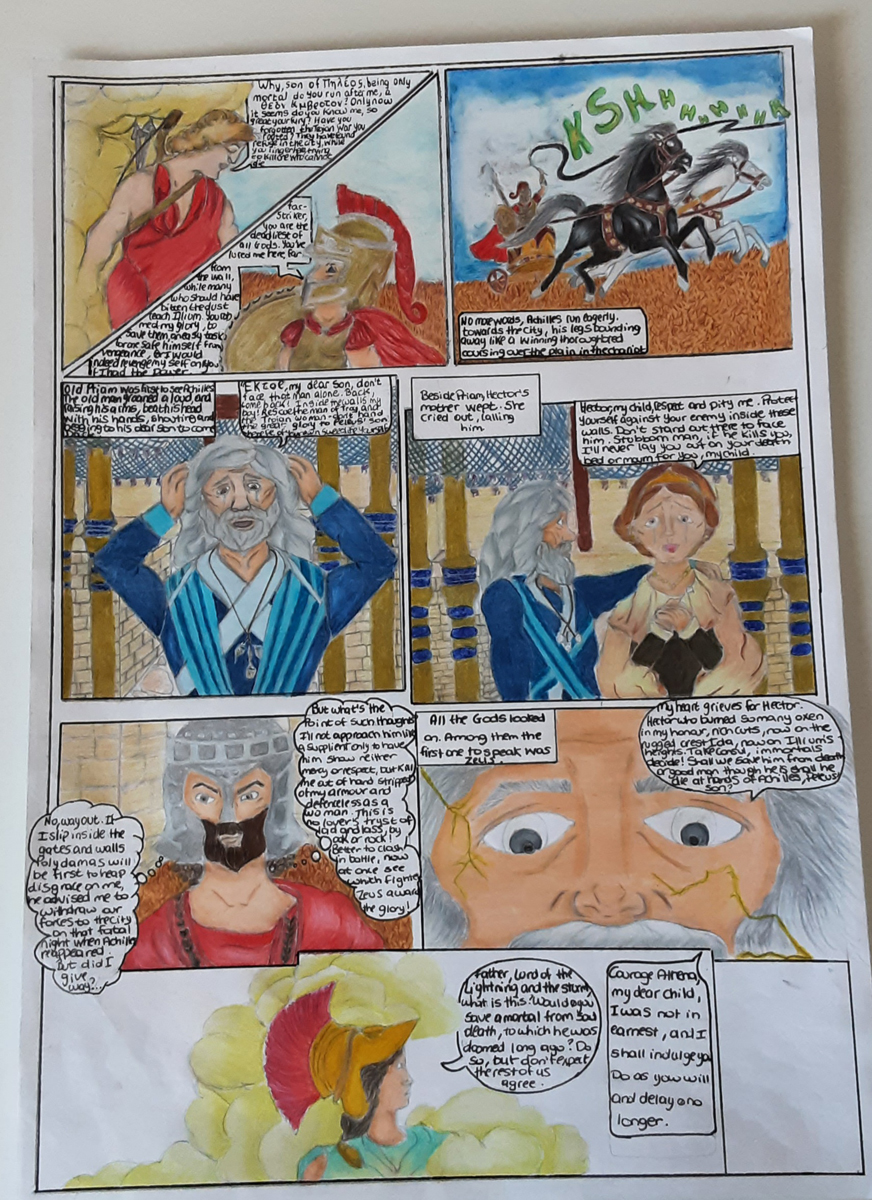

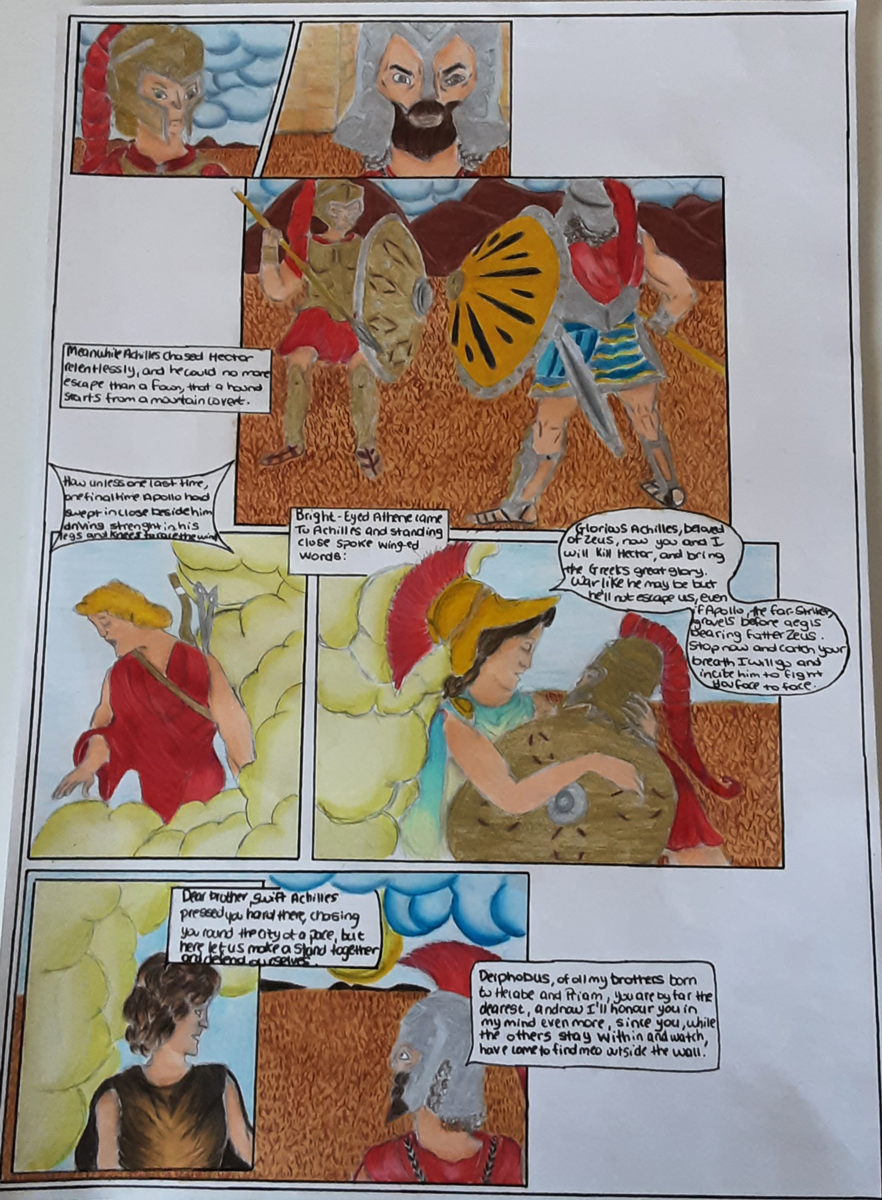

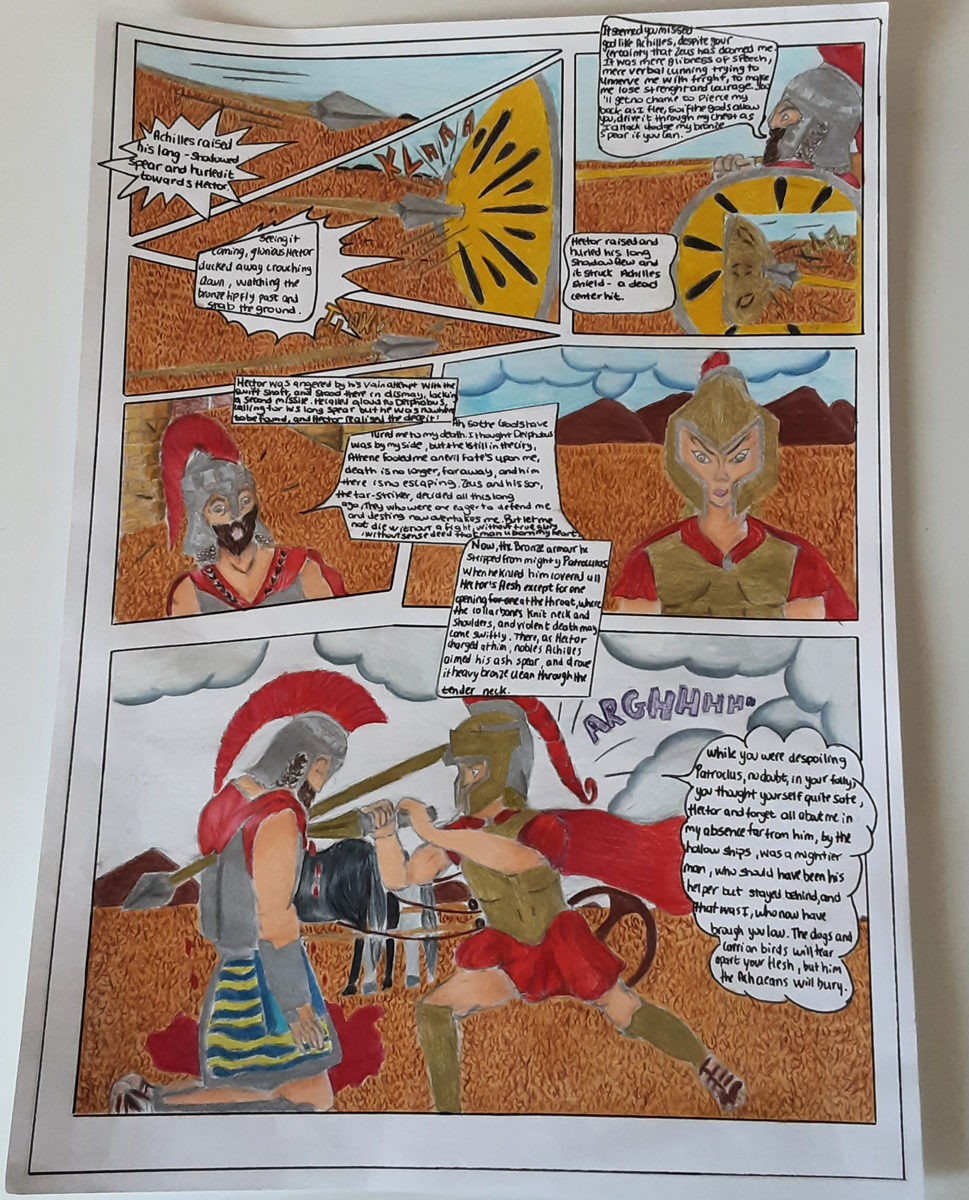

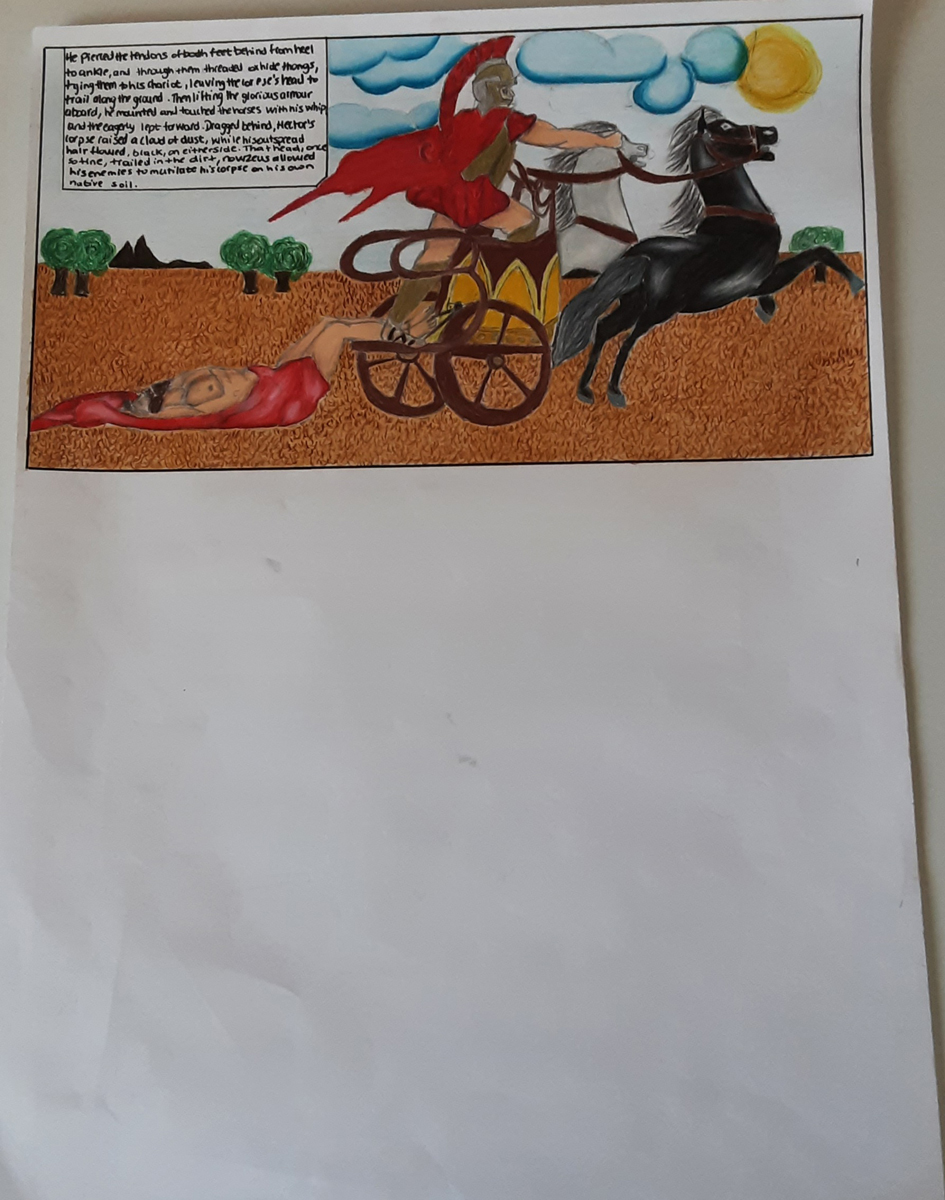

A number of other students produced some impressive pieces, including a Homeric warship model made out of recycled materials, a graphic novel focusing on a retelling of the epic battle between Hector and Achilles, and an original song written from the perspective of King Menelaus — Helen’s wronged husband and consequently one of the central figures leading the Greek army during the Trojan war.

Old Skills and New Passions

Speaking to Serracino, it’s not hard to see how his passion for the subject can be so infectious in a classroom, but he does nothing to claim credit for his students’ impressiveness and instead relishes watching how students discover new talents.

Indeed Vassallo hopes to develop her project into a playable game, Frostick expressed a wish to apply her skill to other classic works, and a number of students said they would adopt similar methods of character analysis to other study-units.

‘I recently ran into a student who had previously done the course, who following his exposure to radio work for his creative project, has continued to work in radio,’ Serracino says with a glint of joy and pride.

‘There is an invisible legacy in these works which we still carry with us nowadays, even in the popular culture we consume now. I have studied Classics for about thirty years now, but they still surprise and inspire me in equal measure,’ he says, adding that the works ultimately prove that the human experience remains the same.

Serracino hopes to adopt similar teaching methods for other courses he oversees in the Classics department to prove how important non-traditional teaching methods can be.’When I was young, I dreamt of creating a live-action movie version of the Iliad, and even if things didn’t pan out exactly that way, seeing these creative renditions of the work from my students feels like I’m fulfilling my dream of breathing new and original life into these masterpieces.’

Author

-

Martina writes on a freelance basis for a number of publications including Think Magazine. She works in children’s publishing in London and has a background in journalism. Previous writing credits include MaltaToday and other other local content writing agencies. Her favourite topics to write about include lifestyle, culture and health issues. She also enjoys interviewing people and learning about new topics as part of her research. She holds an MA in Publishing and previously read for a BA in English at the UM. In her free-time, she can be found sipping tea in coffee shops, reading or trying out new hobbies.

Comments are closed for this article!