During the 1880s, while incarcerated in a Maltese prison, a young man’s desperate thoughts slowly but surely transformed into a series of radical and progressive concepts that would both condemn him and turn him into one of the most overshadowed and pivotal historical figures in Malta’s history.

Manwel Dimech was born in Valletta in 1860. The son of a sculptor, his early childhood was plagued by the harsh living conditions prevalent at the time.

Malta was a colony of the British Empire and a crucial naval base in the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, many of the island’s inhabitants were at the mercy of disease

and poverty, afflictions which also affected the Dimech family. With the death of his father and worsening hardships, the 14-year-old boy found himself involved in thievery that would cause repercussions for years to come, until his death.

‘His whole life was a terrible tragedy. He suffered much from poverty and religious persecution, exile, and prison.’ Mandy Cassar Conti, a postgraduate ethics student reading for a Master’s in Teaching and Learning at the University of Malta, said to THINK about her dissertation on the life of Manwel Dimech. ‘The only option for him to survive was through the criminal world. He therefore used to steal to make a living. He had a rebellious character, and he ended up in bad company.’

At just 17, Manwel Dimech committed involuntary murder together with a friend, following a scuffle with an individual who owed them money. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison, and whilst he himself avoided the gallows, his companion was not so fortunate and was eventually hanged in public. This led to a strong sense of guilt in Dimech. Yet, amid the bleak and dreary existence of prison life, a kindling light shone upon the young convict. It was here that he met his first mentor and teacher, Dun Pietru Pawl Borg. The presence of the prison chaplain, educating and teaching the illiterate Dimech to read and write, proved critical in the young man’s subsequent formative years, which ultimately led to the recognition we know him by today. Cassar Conti explains, ‘Manwel Dimech had found a father figure that was missing in his life at that point. He felt betrayed by his biological father, deeming him a traitor for letting him and his family live in poverty.’

REDEMPTION THROUGH EDUCATION

Unlike his father, Dimech had a very good relationship with his own mother – who visited him on a regular basis and encouraged him to read and study literature. He was exposed to Italian newspapers and began writing several poems in that language, which ended up being published with the assistance of Dun Borg.

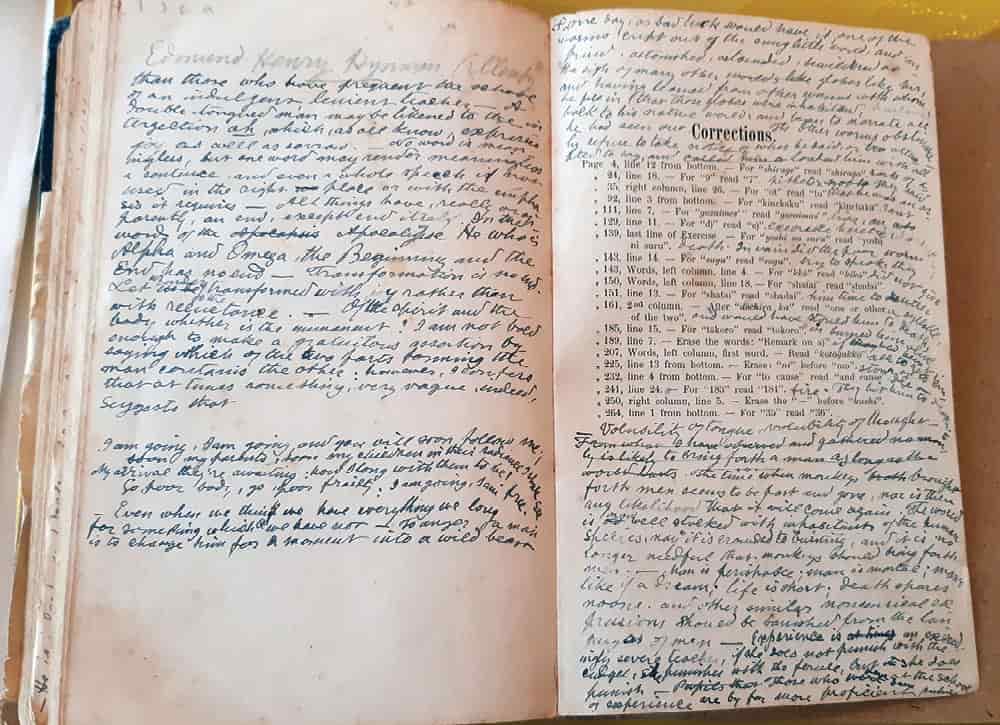

Dimech became literate whilst serving his prison sentence. Despite his early uneducated background, he quickly became a prolific writer and a voracious reader. This helped propel the formation of his radical ideas, which began to simmer at that time. Reading took over his life, and one particular account reveals how he convinced prison authorities that he was suffering from hypochondria – a chronic anxiety about one’s health. He was granted a light in his prison cell, which

enabled him to keep reading late into the night. Light was a crucial concept in Dimech’s thoughts. The symbolic use of illumination, filling the darkness of the mind with knowledge and awareness, signified independence from social shackles or political restrictions; this was attained through education. Only educated individuals were able to comprehend their rights and resist any oppression imposed upon them.

Photos courtesy of Mandy Cassar Conti

After his release in 1897, Dimech made his way to Italy – a country that had started witnessing the rise of the socialist party: the Partito Socialista Italiano (PSI). ‘Few know that Dimech’s profession was that of an educator,’ explains Cassar Conti. ‘He was a teacher. That’s how he made a living in Italy: by teaching French and English. His pedagogy, the way he used to teach, really interests me.’ This enabled Dimech to reach out to people as a public figure, and it was at this time that he became politically active and began to harbour thoughts of an independent Malta – a Republic free from the chains of colonialism. ‘That’s what he’s best known for. He fought against the British.’

Dimech’s thought was influenced by pragmatism (a philosophy that focuses on practical approaches and solutions rather than the theoretical) and this is also reflected in his pedagogy. Instead of, for example, studying the conjugation of verbs by heart or memorising words, which is the traditional method for teaching languages, he contextualised knowledge. ‘In my opinion, learning a phrase in a context is more effective, both in understanding the meaning and also in using it. The traditional method of learning verbs by heart is not apt, because in practice if you are speaking, you are not going to express anything about yourself by reciting the verbs or singular words,’ explains Cassar Conti.

Dimech was also one of the first to strive for Malta’s language. Maltese was largely spoken at that time, especially among the lower classes, but lacked any concrete use in writing. It was Dimech’s belief that this language could unite the people as a nation. Individuals could identify themselves as Maltese, whilst the language could also serve as a political tool, rather than being limited to the exigencies of literature. Dimech wanted his words and messages to reach the working classes. As a result, he began publishing a weekly newspaper, Il-Bandiera tal-Maltin (The Flag of the Maltese), to disseminate and advocate the importance of education to the masses.

With his growth into a fluent speaker, his mastery of various languages, and as the author of several published works, he was able to spread these concepts throughout Malta. Yet, his views of a free and independent Malta did not sit well with the British authorities or the Church. Both of these factions still wielded considerable power over the local population. As a consequence, he was exiled to Egypt, where his presence and radical ideas could be stamped out and removed from the heart of the island.

Despite the terrible conditions he found himself in once again, he persevered in his studies, education, and attainment of knowledge. Already accomplished in four languages as well as some Russian, he spent his exiled years studying Japanese, among other scholarly pursuits. ‘It was a terrible period in his life, and he remained there till his death.’ Despite numerous attempts from family members and friends to bring him back to Malta, such pursuits proved futile, and Dimech eventually died in exile – buried in an unmarked grave.

‘This is why his story really affects me.’ Cassar Conti explains the motivations behind her research: ‘He went through a lot but he kept fighting for social justice. He had this flame and this mission for social justice; he did not just become a cynical individual. He wanted to give back to the people. He wanted to see people rid themselves of that terrible situation they were in.’

PRISON EDUCATION AS REFORMATION

Rehabilitation is a concept that has often been associated with the prison system and with prisoners themselves. Can an individual become a better, more knowledgeable person than when they were incarcerated? Dimech’s story seems to offer a glimmer of hope in this aspect. As Cassar Conti has discovered in her research, education proved the crucial turning point that provided Dimech with rehabilitative benefits. ‘The fact that he had tutors and someone who cared

for him, a mentor, was also crucial in these environments.’

Later on during his prison years, Dimech met his second tutor, Rev. George Wisely, who instilled in the young man a sense of purpose in life. Rev. Wisley believed in pragmatic philosophy, which he passed on to Dimech, who was then able to unify this with his political activism. Cassar Conti believes that ‘the closer prisons can reflect the society out there, the more it can provide rehabilitative properties.’

While Dimech’s incarceration introduced him to father figures and paved the way for a distinguished education, the prison system was unsuccessful in providing him with core social values and behavioural norms. Dimech was not ready to face life, and soon after his release for murder, he was sent back to prison after committing money fraud.

LOOKING AHEAD

Manwel Dimech’s life is both tragic and inspiring. Though failed by the justice system, he is a clear example of the redeeming qualities that a good education and a quest for knowledge can provide. His story has also paved the way for prison reforms in Malta in the years since. The death penalty, which was in existence back then, is now no more.

Depending on the angle through which one chooses to tackle the issue, Dimech’s trials through life may be deemed a success story. He has undoubtedly left an indelible mark on Malta’s history, demonstrating how reforming oneself through sheer determination and with guidance from others enables an individual to strengthen their resolve and contribute beneficially to society. While Dimech was unable to physically free

himself from his oppressors and the situations he was forced into, in the end, he found himself liberated and prevalent through his voice and the written word.

Comments are closed for this article!